List of Sources:

- Young et al., 20201

- Image generated by WordPress AI

Table of Contents:

- Principle of Conservation of Energy (Young et al., 2020)

- Work (Young et al., 2020)

- Kinetic Energy and The Work-Energy Theorem (Young et al., 2020)

- Work and Energy with Varying Forces (Young et al., 2020)

- Power (Young et al., 2020)

Principle of Conservation of Energy (Young et al., 2020)

Principle of Conservation of Energy states that energy can neither be created or destroyed, but can be transformed from one form to another. Thus, the sum of all energy remains the same.

For instance, a battery used to turn a flashlight on does so by converting chemical energy in the battery to electrical energy.

Work (Young et al., 2020)

The total work done on an object can be described by the change in its kinetic energy as a result of a superposition of forces acting on it. Kinetic energy is a quantity that is defined by the object’s mass and speed.

Note: The relationship between work and kinetic energy holds true even when the forces acting on the object are not constant. Thus, in presence of variable forces, work-kinetic energy relationship can be used to solve problems when Newton’s laws would be difficult to utilize.

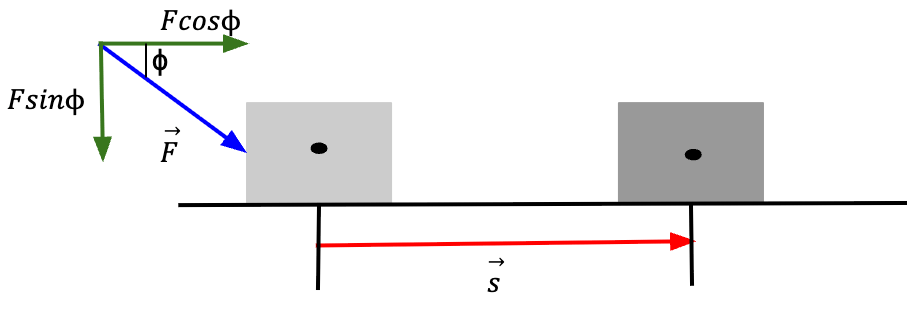

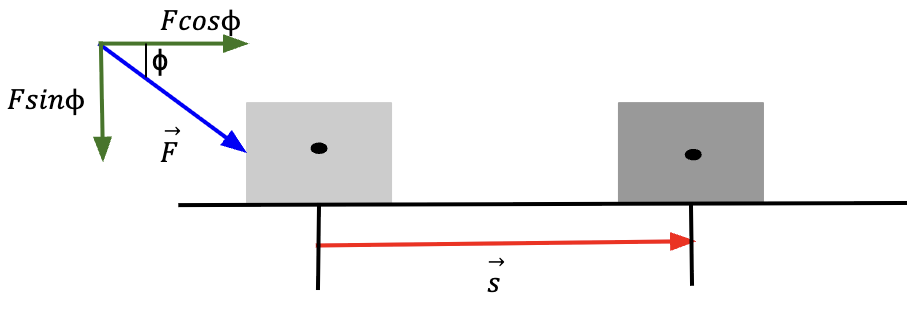

Work when Forces are Constant

When forces applied on an object are constant, work is said to be done when the exerted forces result in motion, or in other words, result in the displacement of the object. Work is directly proportional to the applied force and the amount of displacement that occurs. Consequently, larger the applied force, more is the amount of work done. Similarly, larger is the displacement, more is the work done.

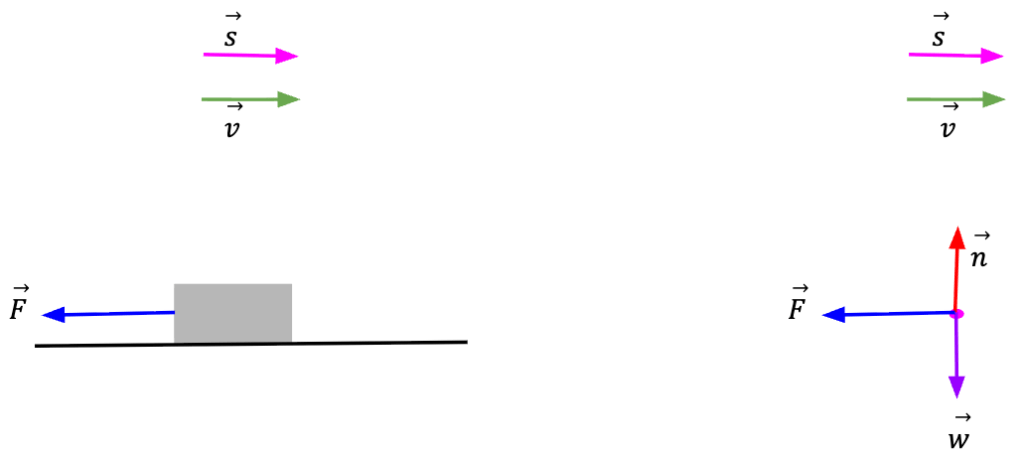

Let’s say you apply a constant force, ![]() to a block such that it undergoes a displacement along a straight line given by

to a block such that it undergoes a displacement along a straight line given by ![]() .

.

Work, W is then defined as the product of magnitude of force, F and magnitude of displacement, s;

W = Fs…..(1)

The SI unit of work is Joule (J).

1 Joule = (1 Newton) (1 meter)…..(2)

If you exert 1 N force on an object along x-direction such that it moves 1 m in the same direction, you do 1 J work on it.

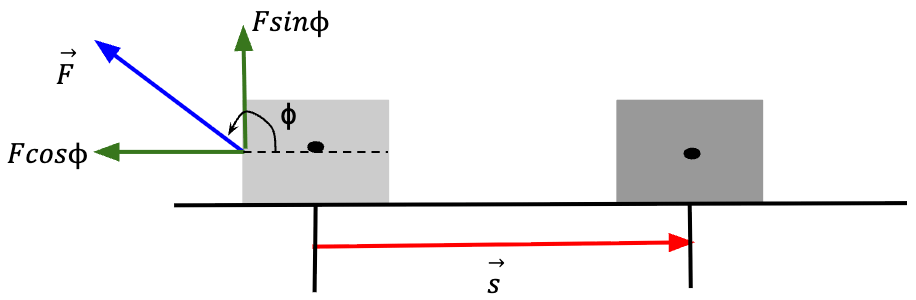

What if you push the block at an angle, ![]() (with respect to the x-direction) with a force,

(with respect to the x-direction) with a force, ![]() such that the block moves a displacement,

such that the block moves a displacement, ![]() in the x-direction.

in the x-direction.

with respect to the x-direction, the x-component of which causes a displacement of magnitude s in the x-direction.

with respect to the x-direction, the x-component of which causes a displacement of magnitude s in the x-direction.Other forces must be acting in the upwards (positive y-direction) to counteract the component of force in the negative y-direction (![]() ). Thus, only the x-component of force given by

). Thus, only the x-component of force given by  contributes to the object’s displacement. Work is then given by;

contributes to the object’s displacement. Work is then given by;

![]() …..(3)

…..(3)

or

![]() …..(4)

…..(4)

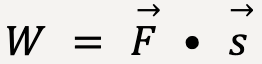

Using the definition of scalar product, we can rewrite equation (4) as:

…..(5)

…..(5)

Thus, work is a scalar quantity. If the angle ![]() is 0°, W=Fs which is in agreement with equation (1).

is 0°, W=Fs which is in agreement with equation (1).

Positive, Negative or Zero Work

Positive Work

When the component of force is in the same direction as the displacement, ![]() is between 0° and 90°, cos

is between 0° and 90°, cos![]() is positive and therefore, work is positive (using equation 4).

is positive and therefore, work is positive (using equation 4).

Negative Work

When the component of force and displacement are in the opposite direction, ![]() is between 90° and 180°, cos

is between 90° and 180°, cos![]() is negative which means that work is negative.

is negative which means that work is negative.

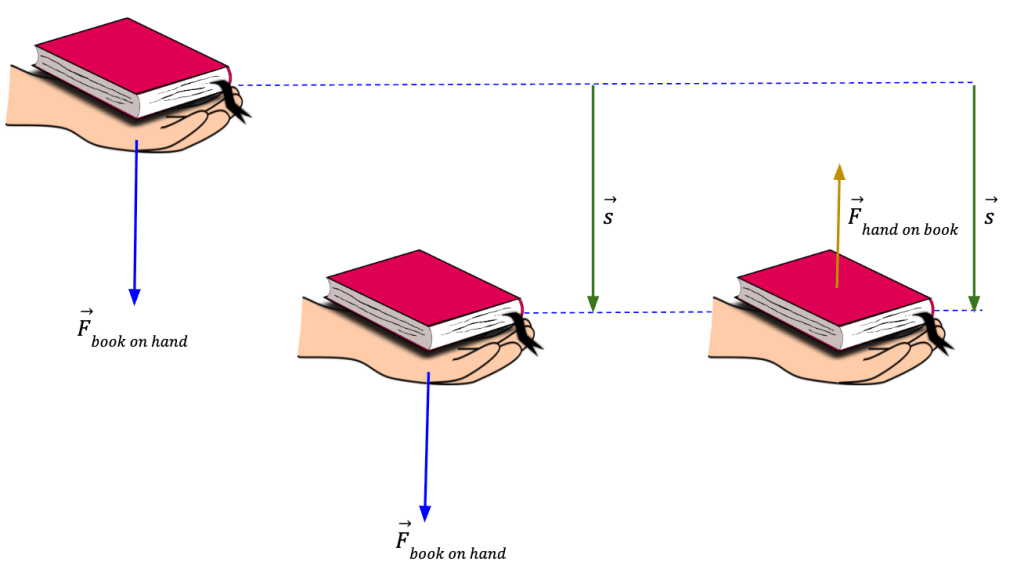

For example, let’s say you are holding a book and you start to lower it towards the ground. Book exerts a force on the hand in the same direction as the hand’s displacement (downwards). Therefore, the work done by the book on the hand is positive. However, according to Newton’s third law of motion, the hand exerts an equal and opposite force on the book, a force that is in opposite direction to the book’s displacement. This force prevents the book from free falling onto the floor. Thus, the work done by the hand on the book is negative.

Zero Work

When force acts perpendicular to the displacement, ![]() is 90°, cos

is 90°, cos![]() is zero and the work done is zero.

is zero and the work done is zero.

Work can be zero if the applied force is zero, displacement is zero or the angle between the component of force and displacement vector is 90°.

Let’s look at a few examples;

For a book sliding on the floor, work done by normal force is zero because it acts perpendicular to the motion or displacement vector.

If you are holding an apple, work done by you on the apple is zero because displacement of the apple is zero even though you apply an upward force on the apple to counteract the force of gravity allowing the apple to be stationary. It is interesting to note that if you are holding something heavier than an apple, say a dumbbell, your arms will start to feel tired even though no work is done2.

Total Work

When multiple forces are acting on an object, work can be calculated using the following two ways:

- Calculate the work done by individual forces and total work done will simply be the algebraic sum of all the work (since work is a scalar quantity).

- Compute the net force which will be the superposition of all the forces acting on the body and then use the net force to calculate the work done.

Kinetic Energy and The Work-Energy Theorem (Young et al., 2020)

Previously we saw a relationship between the total work done on an object and the changes in its position (displacement). Another relationship exists between the total work done on an object and the changes in its speed.

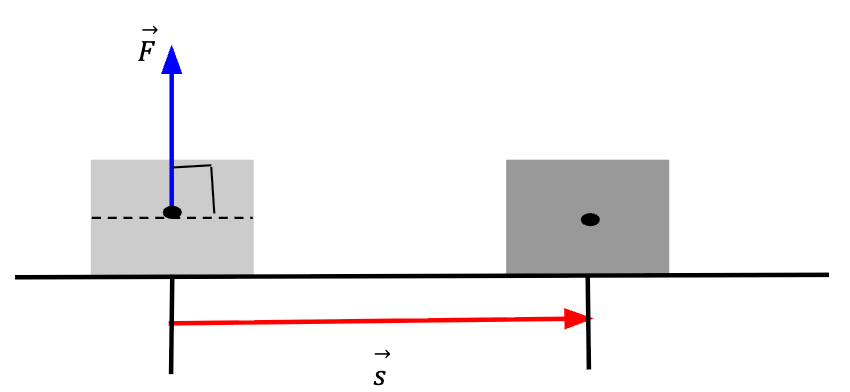

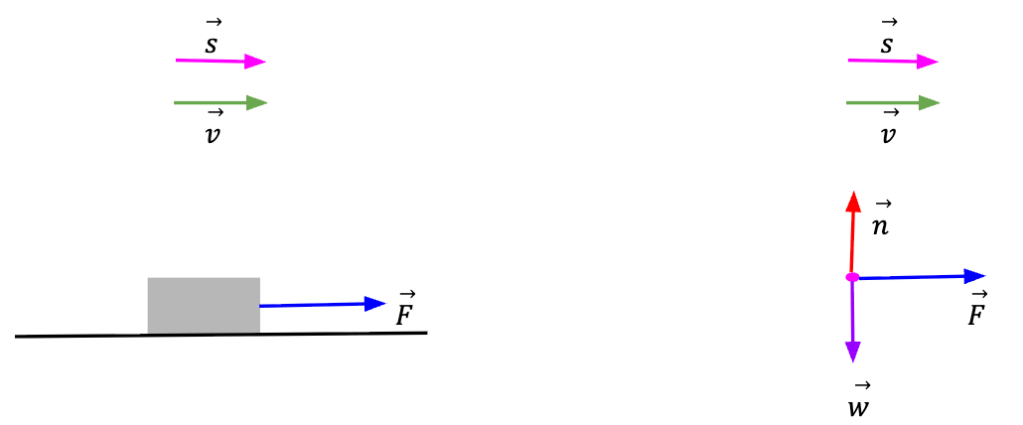

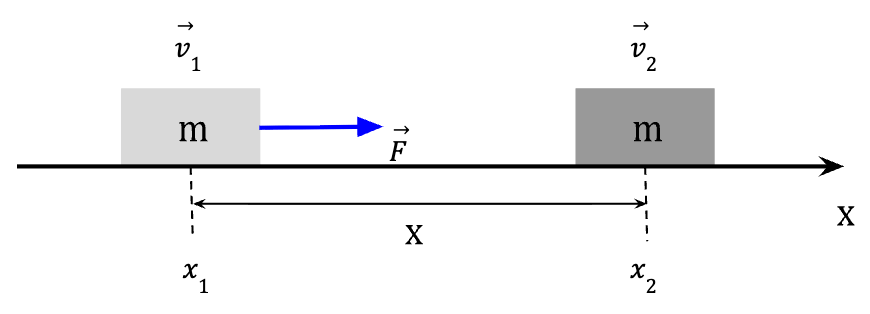

Consider a block moving on a frictionless surface such that a force, ![]() is applied to it. The block undergoes a displacement,

is applied to it. The block undergoes a displacement, ![]() . Since the weight of the block and the normal force are perpendicular to the block’s motion, work done by these forces is zero.

. Since the weight of the block and the normal force are perpendicular to the block’s motion, work done by these forces is zero.

If the exerted force is in the direction of the displacement vector, work done is positive. Additionally, if the force is in the same direction in which the block moves, then according to Newton’s second law, the block will speed up.

This means that if the work done on a moving object is positive (Wtot > 0), then the object will speed up.

However, if the exerted force is in a direction opposite to the displacement vector, work done will be negative. Furthermore, a force in the opposite direction to the described motion will result in the block slowing down.

We can say that if the work done on a block is negative (Wtot <0, then the block will slow down.

Lastly, if the applied force is perpendicular to the displacement vector, work done by this force will equal zero. Additionally, if the net force on the object is zero, then according to Newton’s first law of motion, the block will move with a constant speed.

We can then conclude that if the work done on a block is zero (Wtot = 0), the block will travel with a constant speed.

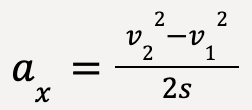

To quantify this relationship between total work done and changes in the speed of the object, consider a block of mass m moving along the positive x-axis under the influence of a constant force, ![]() . Since the force is constant, so is the acceleration which is given by ax. According to Newton’s Second Law;

. Since the force is constant, so is the acceleration which is given by ax. According to Newton’s Second Law;

F = max…..(6)

Using constant-acceleration kinematic equation;

vx2 = v02 + 2ax(x-x0)…..(7)

In this case;

v22 = v12 + 2ax (x2-x1)…..(8)

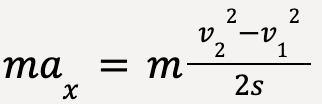

Replacing x2-x1 with s for displacement and rearranging;

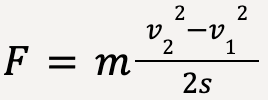

…..(9)

…..(9)

Multiplying both sides of equation (9) with m;

…..(10)

…..(10)

…..(11)

…..(11)

…..(12)

…..(12)

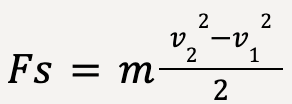

Using equation (1), we know that Fs is the total work done by the applied force F;

…..(13)

…..(13)

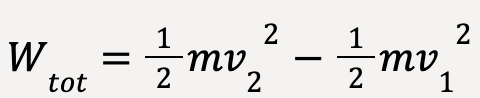

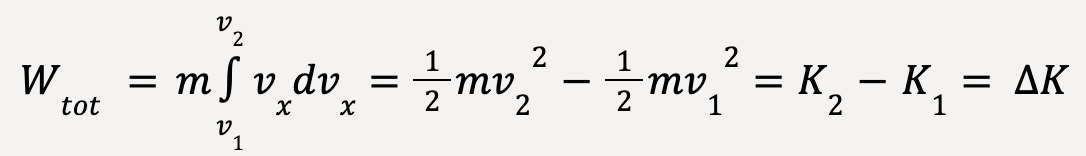

Now the quantity 1/2mv2 is defined as the Kinetic energy (K) of a moving particle, where m is the mass of the particle and v is the speed of the particle.

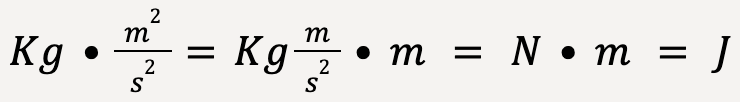

Kinetic energy of a particle is a scalar quantity. Since the mass and speed of a particle are always positive, kinetic energy can never be negative. It is zero when the speed of the particle is zero. The SI unit of kinetic energy is;

Thus, equation (13) can be written as;

Wtot = K2 – K1 = ![]() …..(14)

…..(14)

where K2 is the final kinetic energy of the particle after undergoing a displacement, s, and K1 is the initial kinetic energy of the particle. ![]() is the change in kinetic energy.

is the change in kinetic energy.

Work-Energy Theorem states that the total work done by the net force exerted on an object is equal to the change in the kinetic energy of this moving object.

Equation (14) tells us that if Wtot>0, the final kinetic energy of the particle is greater than the initial kinetic energy. This in turn means that the final speed of the particle is larger than it’s initial speed and the particle is speeding up. This is in agreement with the conclusion drawn from Figure 6.

Similarly, if Wtot<0, the final kinetic energy is less than the initial kinetic energy of the particle and particle must be slowing down.

Finally, if Wtot = 0, then the final kinetic energy must be equal to the initial kinetic energy and the particle must be travelling with constant speed.

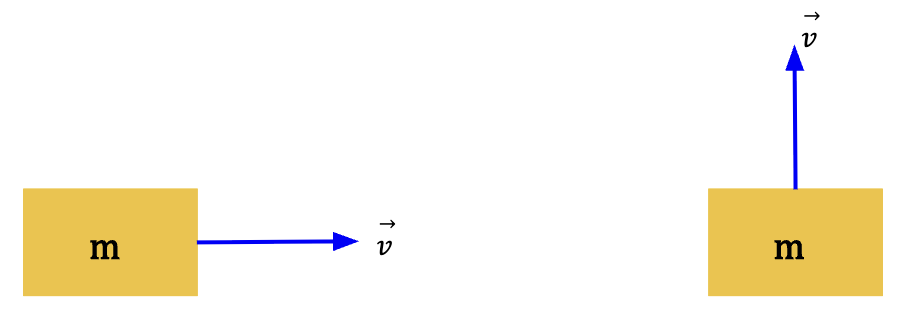

Note 1: The work-energy theorem only gives information about the changes in the speed of the particle, not it’s velocity. This is because kinetic energy does not depend on the direction in which the particle is moving.

Note 2: The work-energy theorem is applicable only in inertial frames of reference because Newton’s laws were used to derive it. The values of Wtot and K1 and K2 can vary in different inertial frames because displacement (s) and speed(v) can be different.

Understanding the Meaning of Kinetic Energy

Kinetic energy (K) can be understood as the total work done (Wtot) to accelerate an object from rest (v0 = 0) to a certain speed, v;

Wtot = K-0 = 1/2mv2…..(15)

Alternatively, kinetic energy (K) can be described as the total work (Wtot) that needs to be done to bring an object travelling with speed v to a complete stop.

Wtot = 0-K = -1/2mv2…..(15)

This is the reason why a cricket player brings his hands backwards while catching a ball because the total work that needs to be done by the player’s hands to stop the ball is equal to the kinetic energy with which it was hit. By increasing the displacement (s) over which the ball travels, he will have to apply less force (F) to match this initial kinetic energy.

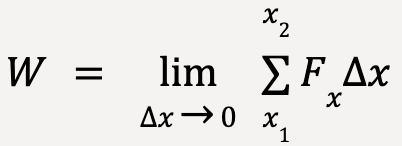

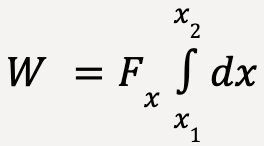

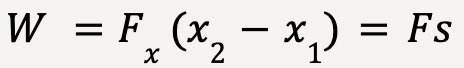

Work and Energy with Varying Forces (Young et al., 2020)

Work-energy theorem holds true even when forces acting on an object are not constant and when the object does not move along a straight path.

Work Done by a Varying Force, Straight Line Motion

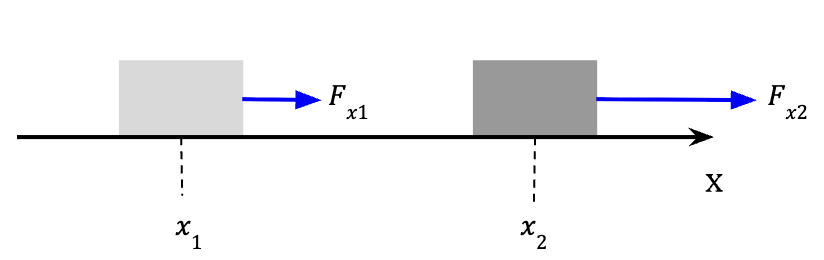

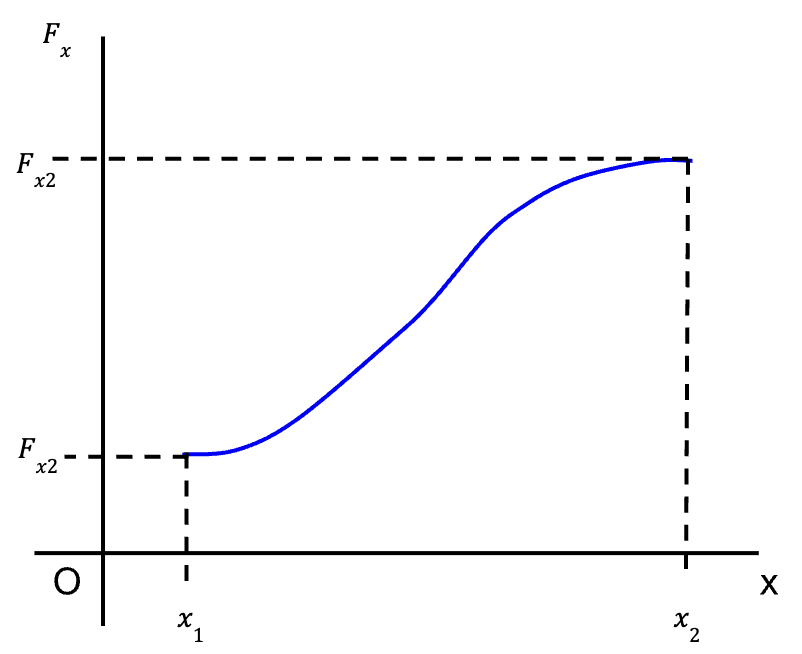

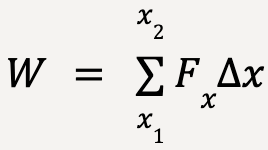

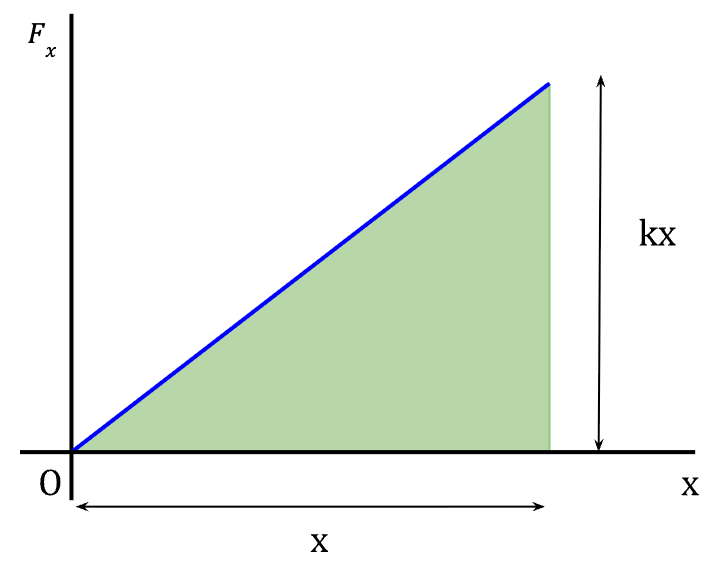

Consider an object moving in a straight line along the positive x-axis (from x1 to x2) such that a variable force, Fx acts on it.

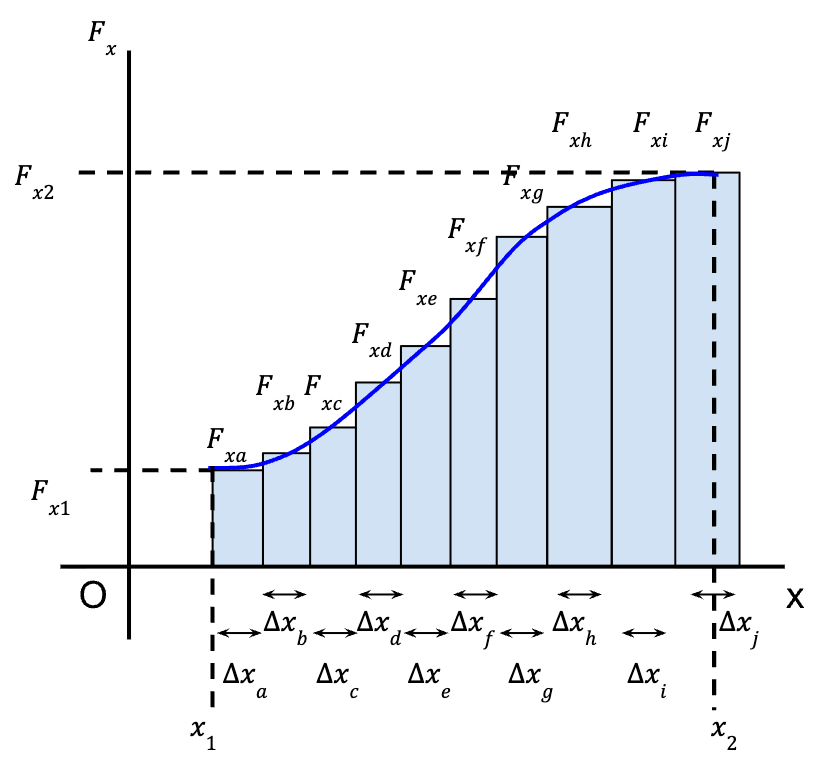

) is approximately constant.

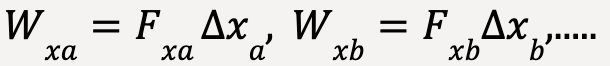

) is approximately constant.If we break the interval from x1 to x2 into short segments of ![]() , then the average of force, Fx over these segments is approximately constant. Work done can then be calculated by multiplying the average force, Fx by each short segment,

, then the average of force, Fx over these segments is approximately constant. Work done can then be calculated by multiplying the average force, Fx by each short segment, ![]() which is equal to the displacement undertaken by the object.

which is equal to the displacement undertaken by the object.

…..(16)

…..(16)

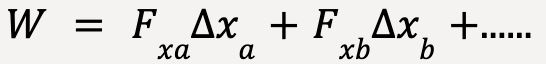

The total work done can then be calculated by computing the algebraic sum of work done over each short segment;

…..(17)

…..(17)

or

…..(18)

…..(18)

Thus, the total work done by the object is equal to the area under the curve representing Fx with respect to x.

In the limit that the ![]() becomes extremely small and the number of segments becomes very large, the area under the curve or total work done is equal to the integral of Fx over the interval from x1 to x2.

becomes extremely small and the number of segments becomes very large, the area under the curve or total work done is equal to the integral of Fx over the interval from x1 to x2.

…..(19)

…..(19)

…..(20)

…..(20)

If the force is constant;

…..(21)

…..(21)

…..(22)

…..(22)

where x2 – x1 = s represents the total displacement undertaken by the object.

We can see that equation (22) is in agreement with equation (1).

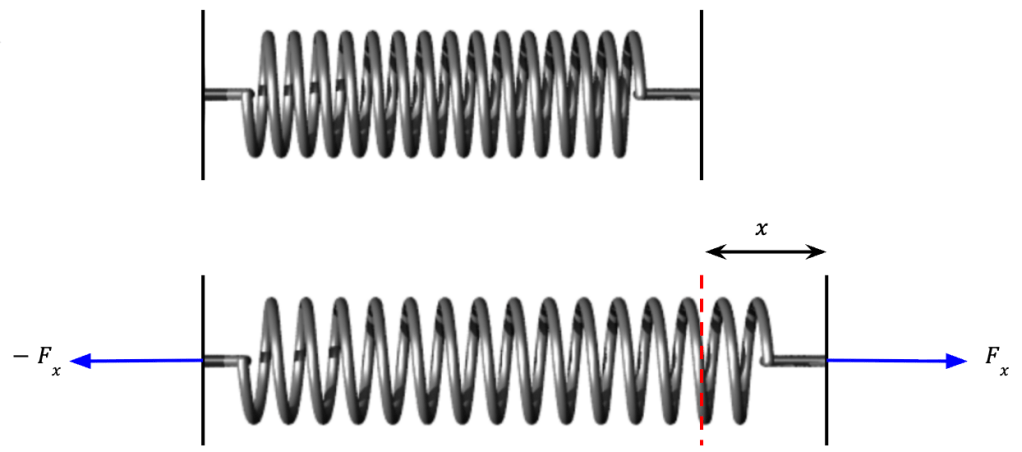

Example: Let’s say we stretch a spring a distance x by applying a force Fx on the right end and an equal and opposite force, -Fx on the left end.

If the applied force is not too large, the magnitude of Fx is directly proportional to the amount by which the spring is stretched, in this case, x.

Fx = kx…..(23)

k is referred to as the force constant (or spring constant) with SI units of N/m. Larger the value of k, stiffer will be the spring. Equation (23) is referred to as Hooke’s Law after Robert Hooke who first observed this relationship in springs.

As we continue to apply equal and opposite forces on the two ends of the spring, if we then hold the left end stationary while stretching the spring on the right end, the force on the left does no work but the force on right does.

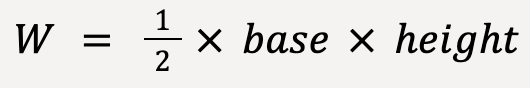

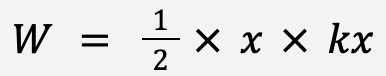

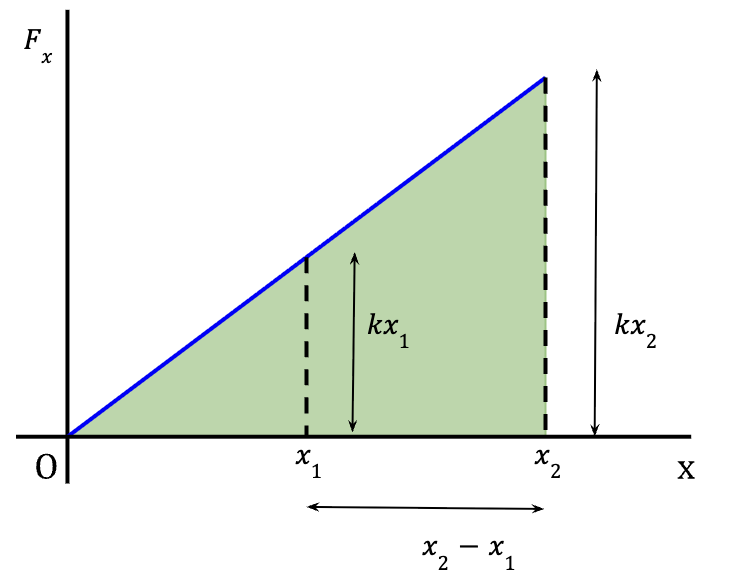

The force applied to the spring can be represented as a straight line (Figure 16) since the relationship between Fx and x is linear. As discussed earlier, the area under the graph represents the work done on the spring by the applied force. Since the area under the graph forms a traingle;

…..(24)

…..(24)

…..(25)

…..(25)

…..(26)

…..(26)

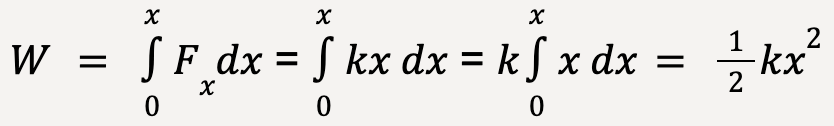

Alternatively, using equation (20);

…..(27)

…..(27)

which is in agreement with equation (26). This result can also be interpreted as the average force (1/2 kx) multiplied by the elongation distance x.

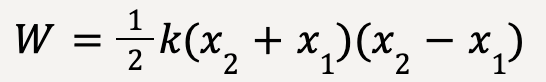

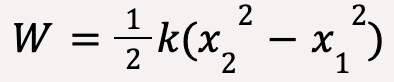

More generally, if the spring was originally stretched by a distance x1 and it is further stretched to a distance x2, work done by the applied force is;

…..(28)

…..(28)

Graphically,

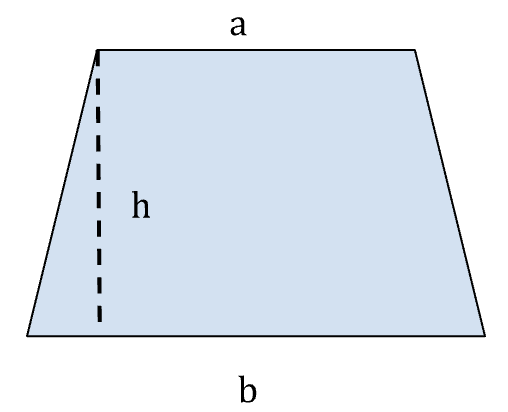

The formula for the trapezoid as shown in figure 18 is given by;

…..(29)

…..(29)

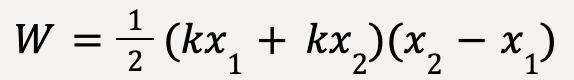

Work done by the applied force is equal to the area of the trapezoid as shown in figure 17;

…..(30)

…..(30)

…..(31)

…..(31)

Using the identity (a+b)(a-b) = a2 – b2;

…..(32)

…..(32)

…..(33)

…..(33)

which is in agreement with equation (28).

Note 3: Hooke’s law is also applicable to springs that are compressed. In that case, if the force is applied to the left, the spring will get compressed in the same direction. Both Fx and x will be negative but work done will still be positive because displacement is in the same direction as the applied force.

Note 4: If you stretch a spring by applying a force Fx, then according to Newton’s third law, the spring applies an equal and opposite force on you given by -Fx. So if the work done by you on the spring is Wyou on spring = 1/2kx2, then the work that the spring does on you is Wspring on you= -1/2kx2.

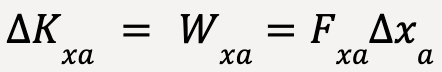

Work-Energy Theorem for Straight-Line Motion, Varying Forces

Work-energy theorem, Wtot = K2 – K1 holds true even when the applied forces are changing with position.

Consider a particle moving along the positive x-direction such that a variable force, Fx is applied to it. Similar to what is done in Figure 13, we can divide displacement x2-x1 into multiple smaller segments of length ![]() . Since the value of Fx over each segment is approximately constant, work-energy theorem can be applied to each

. Since the value of Fx over each segment is approximately constant, work-energy theorem can be applied to each ![]() .

.

For segment  ;

;

…..(34)

…..(34)

Since change in kinetic energy is a scalar quantity, the total change between x1 and x2 is the algebraic sum of change in kinetic energy over each segment, ![]() ;

;

…..(35)

…..(35)

Thus, even when force is not constant, work-energy theorem is applicable.

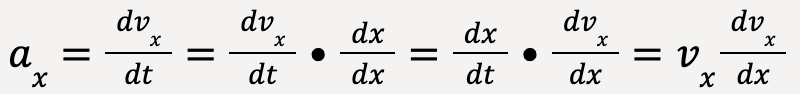

Alternatively;

Using the chain rule of derivatives, the acceleration along the x-axis, ax can be written as;

…..(36)

…..(36)

From equation (20), the total work done by a variable force is given by;

…..(37)

…..(37)

Using Newton’s second law of motion;

…..(38)

…..(38)

Since mass (m) is constant and when x = x1, vx=v1, similarly when x=x2, vx=v2;

…..(39)

…..(39)

which again proves that work-energy theorem can be applied to cases when force is not constant.

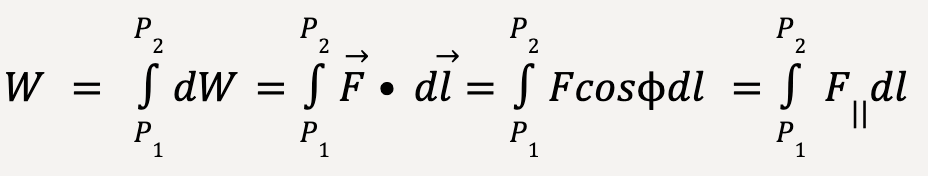

Work-Energy Theorem for Motion along a Curve

Consider a particle moving from P1 to P2 along a curved path such that a variable force (changing both in magnitude and direction), ![]() acts on it. We break the curve into small displacements given by

acts on it. We break the curve into small displacements given by  , and each displacement is tangent to the path taken by the particle.

, and each displacement is tangent to the path taken by the particle.

has a component parallel to displacement

has a component parallel to displacement  and a component perpendicular to

and a component perpendicular to  .

.Since only the force along the displacement vector does work, the applied force, ![]() is broken down into a parallel (

is broken down into a parallel ( ) and perpendicular (

) and perpendicular ( ) component as shown in figure 20 such that the angle between

) component as shown in figure 20 such that the angle between ![]() and

and  is equal to

is equal to ![]() .

.

The small amount of work done over each displacement is given by;

…..(40)

…..(40)

The total work done by force, ![]() on the particle as it moves from P1 to P2 is given by;

on the particle as it moves from P1 to P2 is given by;

…..(41)

…..(41)

Thus, work done is equal to the line integral of dot product between the applied force ![]() and displacement

and displacement  .

.

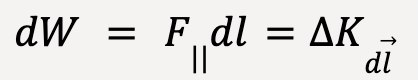

During the short displacement  , force is approximately constant. This means that the change in kinetic energy over this small displacement is equal to the work done by the applied force.

, force is approximately constant. This means that the change in kinetic energy over this small displacement is equal to the work done by the applied force.

…..(42)

…..(42)

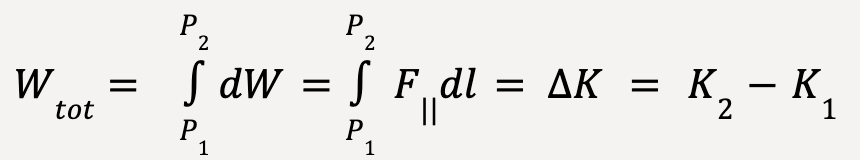

Since kinetic energy is a scalar quantity, the total change from P1 to P2 is the algebraic some of all changes over each segment;

…..(43)

…..(43)

Thus, work-energy theorem holds true whether the path is straight or curved and whether the applied force is constant or not.

Power (Young et al., 2020)

The definition of work done, does not take into account the time taken to do a given amount of work. If you lift a book by doing 10J of work on it, it does not matter whether you lifted it in 1s or 10s, the amount of work done will stay the same, 10J.

The relationship between work done and the time it took to do that work is given by power.

Power is defined as the “time rate at which work is done”. It is a scalar quantity.

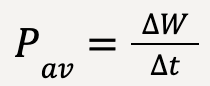

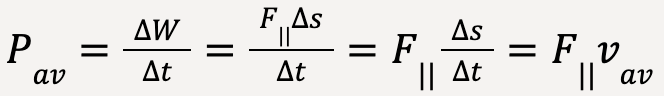

Average power, Pav is given by;

…..(44)

…..(44)

where ![]() is the work done during time interval

is the work done during time interval ![]() .

.

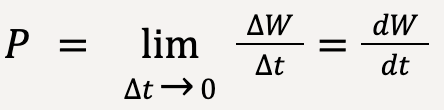

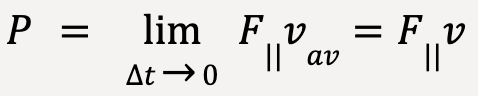

When the rate of doing work is not constant, instantaneous power, P can be calculated as follows:

Let’s say the time interval ![]() approaches zero, in this limit, power is equal to the derivative of work with respect to time;

approaches zero, in this limit, power is equal to the derivative of work with respect to time;

…..(45)

…..(45)

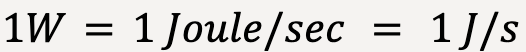

The SI unit of power is watt (W).

…..(46)

…..(46)

Other commonly used units of power;

| Unit | Equivalent to how many watts (W)? |

| 1 kilowatt (kW) | 103 W |

| 1 megawatt (MW) | 106 W |

| 1 horsepower (hp) | 746 W |

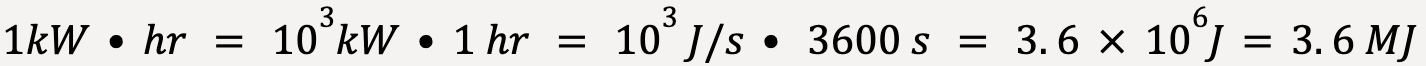

Commercially, the unit commonly used for electrical energy is kilowatt-hour. A kilowatt-hour is the amount of work done per hour when power is 1 kilowatt (kW);

…..(47)

…..(47)

Note 5: Kilowatt-hour is not a unit of power. It is either a unit of work or energy.

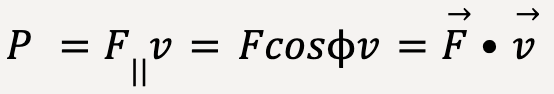

For the purposes of mechanics, a relationship can be established between power, force and velocity. Consider a force, ![]() that acts on an object as it displaces by

that acts on an object as it displaces by  , then the average power is given by;

, then the average power is given by;

…..(48)

…..(48)

In the limit that ![]() goes to zero, instantaneous power can be calculated as;

goes to zero, instantaneous power can be calculated as;

…..(49)

…..(49)

where v is the magnitude of instantaneous velocity.

…..(50)

…..(50)

Thus, instantaneous power can also be expressed as the scalar product of applied force, ![]() and object’s instantaneous velocity, v.

and object’s instantaneous velocity, v.