List of Sources:

- Young et al., 20161

- NIST, 20202

- Images by WordPress AI and Pexels.com

Table of Contents:

- Standards and Units (Young et al., 2016)

- Uncertainty and Significant Figures (Young et al., 2016)

- Vectors (Young et al., 2016)

- Common Errors in Understanding (Young et al., 2016)

Standards and Units (Young et al., 2016)

The International System (SI) outlines the standard units of measurement3, which are universal. Fundamental quantities like time, length or mass can only be defined by stating how to measure them. Quantities like speed can then be defined by utilizing two or more of these fundamental quantities.

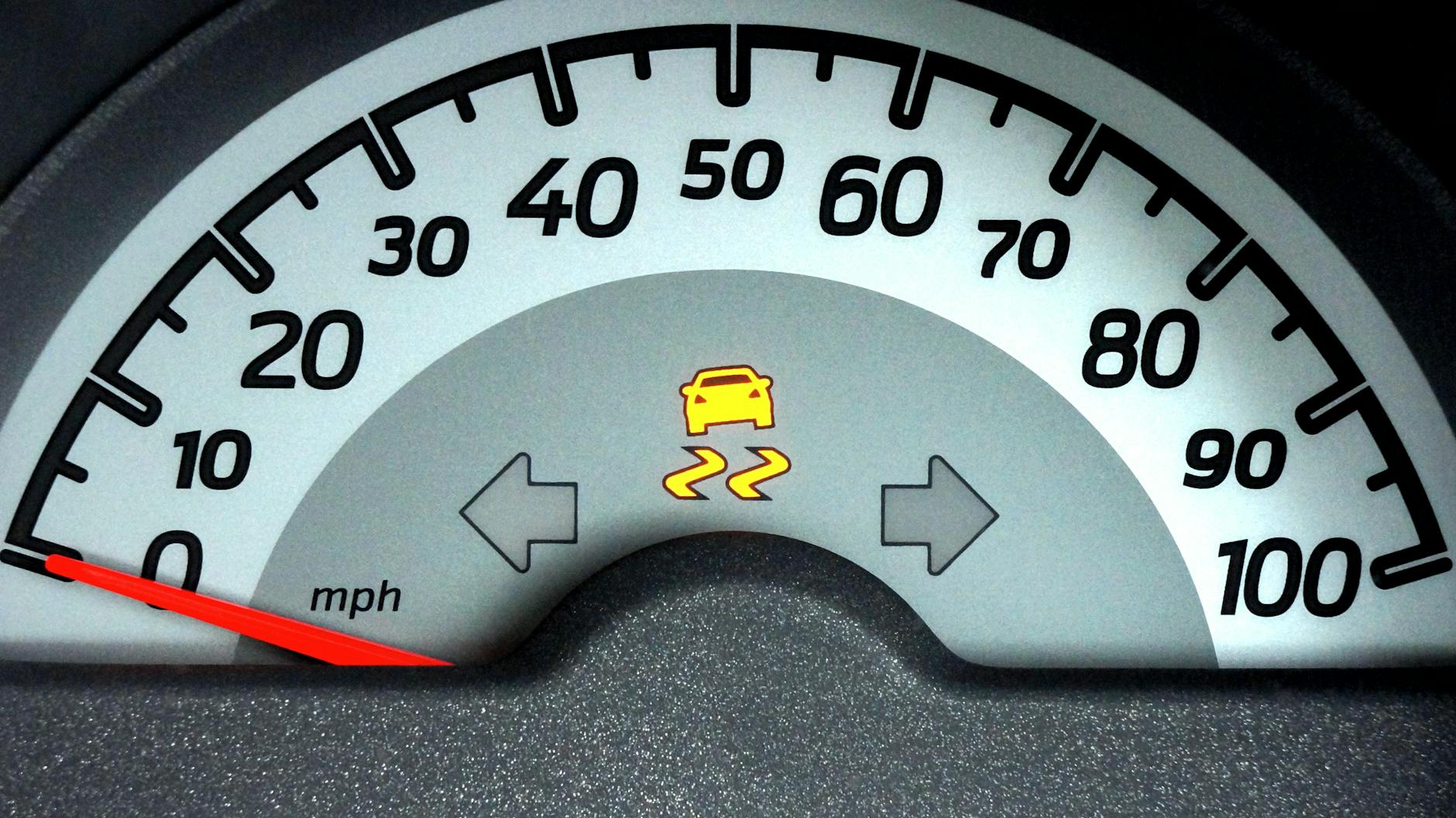

- A second is defined by the atomic clock. When cesium-133 atom is bombarded with microwave radiation of a specific frequency, the cesium atom transitions from one energy state to another.

- The two energy states refer to the reversal of spin of the outermost electron in the cesium atom.

- Specific frequency depends on the energy difference between the two states and is determined to be 9,192,631,770 cycles per second;

.

. - One second is then defined as the time required by the microwave radiation to complete 9,192,631,770 cycles.

- A meter is the distance in vacuum travelled by light in 1/299,792,458 second.

- Speed of light in vacuum is measured to be 299,792,458 m/s.

- Light travels 299,792,458 meters in 1 second. This means that it travels 1 meter in 1/299,792,458 second.

- A kilogram is defined by the value of Planck’s constant (NIST, 2020), h = 6.62607015 ×10−34 J/s = 6.62607015 ×10−34 kg m2 s-1 .

- m is defined by speed of light and s is defined by the frequency of microwave radiation needed for 133Cs transition (as stated above).

Uncertainty and Significant Figures (Young et al., 2016)

Uncertainty

When we take measurements, the measurement is reliable only to the nearest possible value that the measuring device can measure. For example, measurements made using a centimeter scale are reliable up to the nearest centimeter. If the scale yields a result of 15.0 cm, it is possible that the actual length is 14.8 cm or 15.1 cm.

Uncertainty (also referred to as the error) is defined as the maximum possible difference between the measured value and the true value. Smaller the uncertainty, larger is the accuracy of the measured value.

| Uncertainty | 25.0+/-0.3 m | The true value lies somewhere between 24.7 m and 25.3 m. |

| Fractional error/uncertainty | 0.3/25.0 = 0.012 | Uncertainty divided by the measured value. |

| Percent error/uncertainty | 0.012*100% = 1.2% | A scale that measures 25.0 m +/- 1.2% means that the true length differs from 25.0 m by at most 1.2%. |

Significant Figures

Sometimes, measurements do not include uncertainties and uncertainty is implicitly derived from the number of significant digits listed.

| Measurement | Significant Digits | Uncertainty |

| 2.85 m | 3 | ~0.01 m |

| 158 km | 3 | ~1 km4 |

| 0.59 m | 25 | ~0.01 m |

| 0.590 m | 3 | ~0.001 m |

| 5.00 cm | 36 | ~0.01 cm |

| 5900 km | 2 or 3 or 4 | ~100 km 0r ~10 km or ~1 km7 |

| 4800.056 km | 78 | ~0.001 km |

| 9.25 x 10-4 m/s | 3 | ~0.000001 m/s or 0.01 x 10-4 m/s |

Method: In 2.85 m, there are 3 significant digits. The last one is in the hundredths place and so the uncertainty is ~0.01 m.

Multiplication or Division

When two numbers are multiplied or divided, the resulting value can not have significant figures that are more than the factor with the least number of significant digits.

For example: 5.9678 x 0.43 = 2.6 (Max of two significant figures as highlighted)

Addition or Subtraction

When two numbers are added or subtracted, uncertainty in the resulting value is given by the number with the largest uncertainty (or least number of digits after the decimal point).

For example: 4.876 + 3.2 + 0.25 = 8.3 (Only one digit after the decimal allowed)

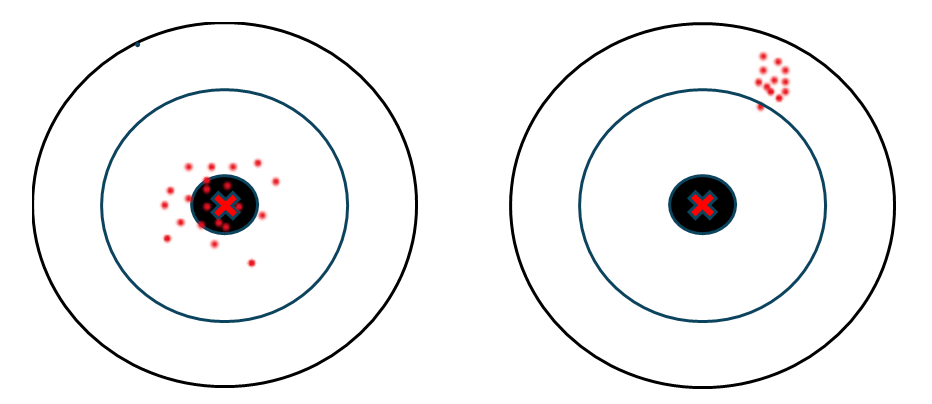

Precision vs. Accuracy

A measurement can have 8 significant figures making it very precise but the result can still be inaccurate if the equipment is faulty. A measurement can have two significant figures, making it not so precise but the result can be very close to the true value making it highly accurate. The goal of measurements is to be both accurate and precise.

Vectors (Young et al., 2016)

A vector is a physical quantity that has both a magnitude and a direction. It is different from a scalar quantity, which only has a magnitude but no direction associated with it.

Examples of scalar quantities: distance, time, temperature, mass, density, energy, speed, voltage, current, etc.

Examples of vector quantities: velocity, force, displacement, acceleration, momentum, electromagnetic field, etc.

Distance is a scalar quantity because it simply tells you how far an object moved. On the other hand, displacement is defined as the change in an object’s position, which includes how far the object moved and in what direction. Hence, displacement is a vector quantity.

Vector Notations

A vector is denoted by placing an arrow on top of the letter or symbol as shown below:

The magnitude of a vector (scalar quantity, always positive) is represented as follows:

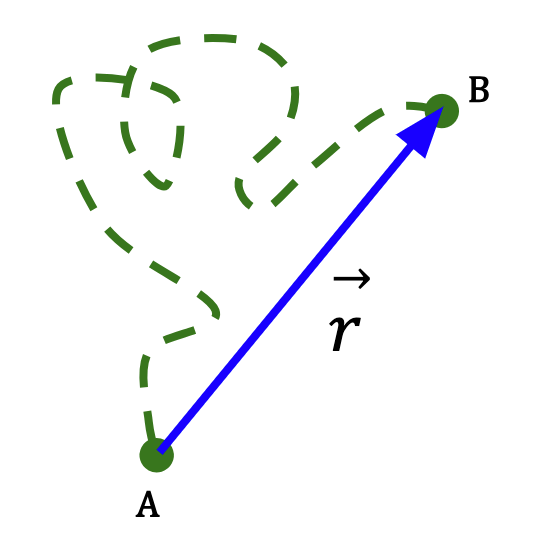

Representation of a Vector

A vector is represented using an arrowhead with the tail at the starting point and the tip at the final point. The length of the arrow is representative of the magnitude of the given vector and the direction of the arrow aligns with the direction of the given vector.

In Figure 2, displacement vector is shown by the blue arrow, a straight line from point A to B. Displacement vector is independent of the path taken by the object. In this case, distance travelled (green dotted line) is much greater than the magnitude of the displacement vector. If the object started at point A and subsequently returned to point A, the displacement for the whole trip will be zero but distance will be a non-zero quantity.

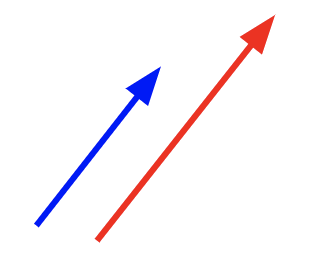

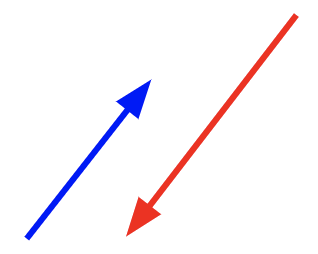

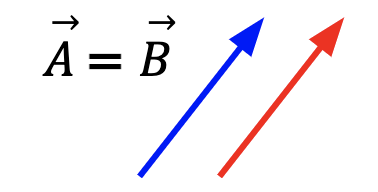

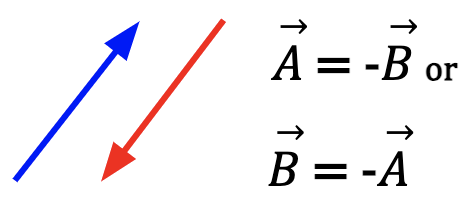

Parallel vs. Antiparallel vs. Equal Vectors vs. Negative of a Vector

| Parallel Vectors | Antiparallel Vectors | Equal Vectors | Negative of a Vector |

| Two vectors are said to be parallel, if they have the same direction | Two vectors are said to be antiparallel, if they have opposite direction | Two vectors are said to be equal, if they have the same magnitude and are in the same direction | When two vectors have the same magnitude but opposite direction |

| Vectors can have different magnitudes | Vectors can have different magnitudes | Vectors can have different spatial location | Vectors can have different spatial location |

|  |  |  |

Vector Addition and Subtraction

Vector Addition

What does it mean to add two vectors, say displacement and displacement

and displacement  ?

?

Let’s say an object moves a certain length along a certain direction and the displacement is given by,  . It then goes under a second displacement given by

. It then goes under a second displacement given by  . The resulting displacement,

. The resulting displacement, , is the same as if the object had started at the initial point of

, is the same as if the object had started at the initial point of  and stopped at the final position of

and stopped at the final position of  . In other words,

. In other words,  is the vector sum or resultant vector of vectors

is the vector sum or resultant vector of vectors  and

and  (See Error #1).

(See Error #1).

=

=  +

+  ……(1)

……(1)

Vectors can be added using three methods as illustrated below:

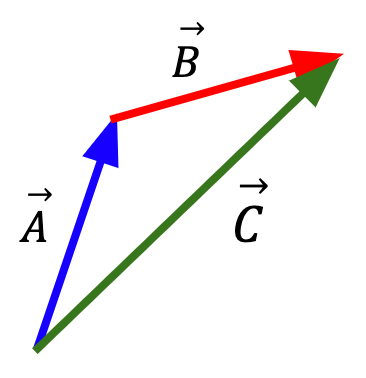

Method 1:

Figure 3: Draw  using an arrow, the length of which represents the magnitude, and it is in the direction of

using an arrow, the length of which represents the magnitude, and it is in the direction of . Next, draw

. Next, draw  such that the tail of this vector originates at the tip of

such that the tail of this vector originates at the tip of  . Finally, the resultant vector

. Finally, the resultant vector , can be drawn with the tail that coincides with the tail of

, can be drawn with the tail that coincides with the tail of  and tip that coincides with the tip of

and tip that coincides with the tip of  .

.

This is the most used method that reduces the likelihood of making errors.

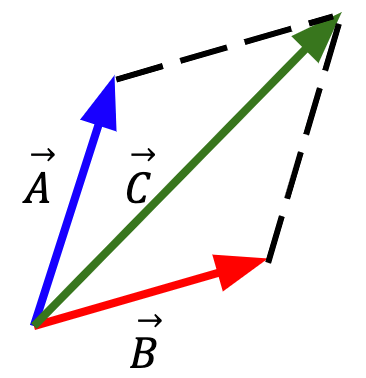

Method 2:

Figure 4: Method 1 can be reversed such that you begin with  , followed by placing the tail of

, followed by placing the tail of  at the tip of

at the tip of  , yielding a resultant vector

, yielding a resultant vector  which originates at the tail of

which originates at the tail of  and ends at the tip of

and ends at the tip of  . This method works because you will notice that reversing the order of

. This method works because you will notice that reversing the order of  and

and  does not affect the magnitude or direction of

does not affect the magnitude or direction of  , which stays the same. Thus, vector addition is commutative, which means that

, which stays the same. Thus, vector addition is commutative, which means that  +

+  =

=  +

+  .

.

Method 3:

Figure 5: Place vectors  and

and  such that their tails coincide. The lengths of these two arrows represent the two sides of a parallelogram. Complete the parallelogram (as shown using dotted black lines) and

such that their tails coincide. The lengths of these two arrows represent the two sides of a parallelogram. Complete the parallelogram (as shown using dotted black lines) and  is placed along the diagonal of this completed parallelogram. Note: The tails of the three vectors should coincide.

is placed along the diagonal of this completed parallelogram. Note: The tails of the three vectors should coincide.

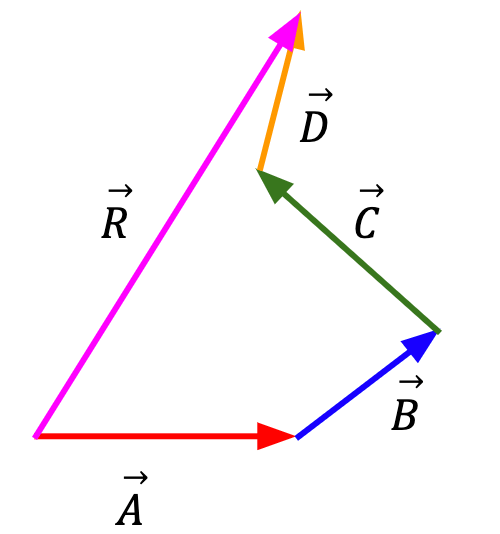

What if you want to add more than two vectors, say  ,

,  ,

,  &

&  ?

?

There are two methods with which you can add multiple vectors.

Method 1:

=

=  +

+  +

+ +

+ ……(2)

……(2)

Figure 6: When adding multiple vectors, arrange them such that the tail of the next vector begins at the tip of the previous vector. The resultant vector,  is given by the arrow that originates at the tail of the first vector and ends at the tip of the last vector.

is given by the arrow that originates at the tail of the first vector and ends at the tip of the last vector.

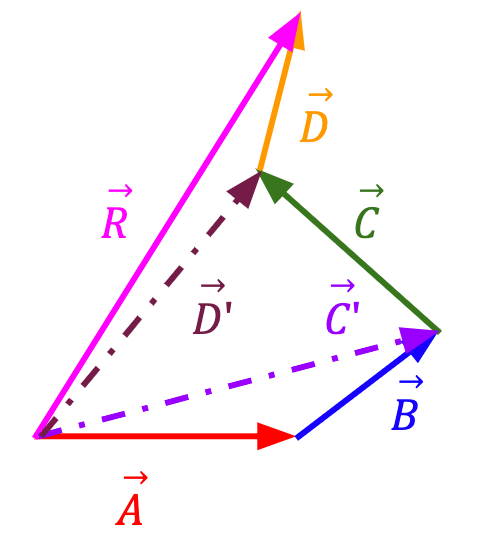

Method 2:

Figure 7: Alternatively, you can first add two vectors which will yield a resultant vector,  . Next, add

. Next, add  and

and  to get

to get  . Finally, add

. Finally, add  and

and  to get resultant vector,

to get resultant vector,  which has the same magnitude and direction as the resultant vector in Figure 6.

which has the same magnitude and direction as the resultant vector in Figure 6.

Figure 8: Notice that you could first add  and

and  to yield a resultant vector

to yield a resultant vector  . Next, add

. Next, add  and

and  to get

to get  . The subsequent steps are the same as Figure 7. This means that,

. The subsequent steps are the same as Figure 7. This means that,

=

= +

+  =

=  +

+  ….(3)

….(3)

This is because vector addition is associative.

+ (

+ ( +

+ ) = (

) = ( +

+  )+

)+ …(4)

…(4)

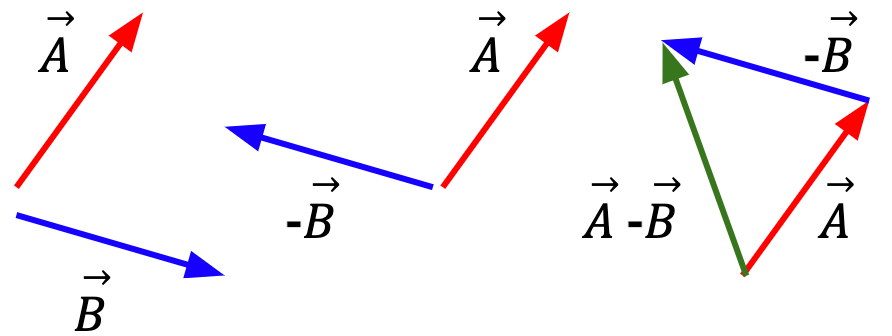

Vector Subtraction

Vectors can be subtracted using two methods.

Method 1:

Think of vector subtraction as vector addition. Instead of subtracting  from

from  , add –

, add – to

to  . In other words,

. In other words,

–

–  =

=  + (-

+ (- )……(5)

)……(5)

This way, the rules of vector addition apply. First, determine the negative of  and then add it to

and then add it to  as shown in Figure 9.

as shown in Figure 9.

This method reduces confusion and the likelihood of making an error.

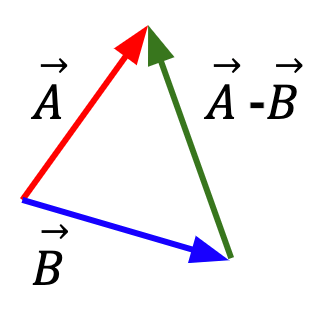

Method 2:

Figure 10: Connect the two vectors tail to tail and the resultant vector originates at tip of the second vector and ends at the tip of the first vector. The resultant vector is the same as the one produced in Figure 9.

Multiplying a Vector by a Scalar

Vectors can be multiplied by scalar quantities as follows:

= k

= k …..(6)

…..(6)

- The value of scalar, k, is multiplied by the magnitude of

to get the magnitude of

to get the magnitude of  .

.

- If k > 1,

increases. For example,

increases. For example,  = 2

= 2 means that

means that  is twice as big as

is twice as big as  .

. - If 0 <k < 1,

decreases. For example,

decreases. For example,  = 0.5

= 0.5 means that

means that  is half of

is half of  .

.

- If k > 1,

- The sign of scalar k, gives information regarding the direction of the vector,

.

.

- If k is positive,

is in the same direction as

is in the same direction as  .

. - If k is negative,

is in the opposite direction as

is in the opposite direction as  .

.

- If k is positive,

Components of a Vector

Instead of using vector diagrams, vectors can be easily added using the components of the vector given.

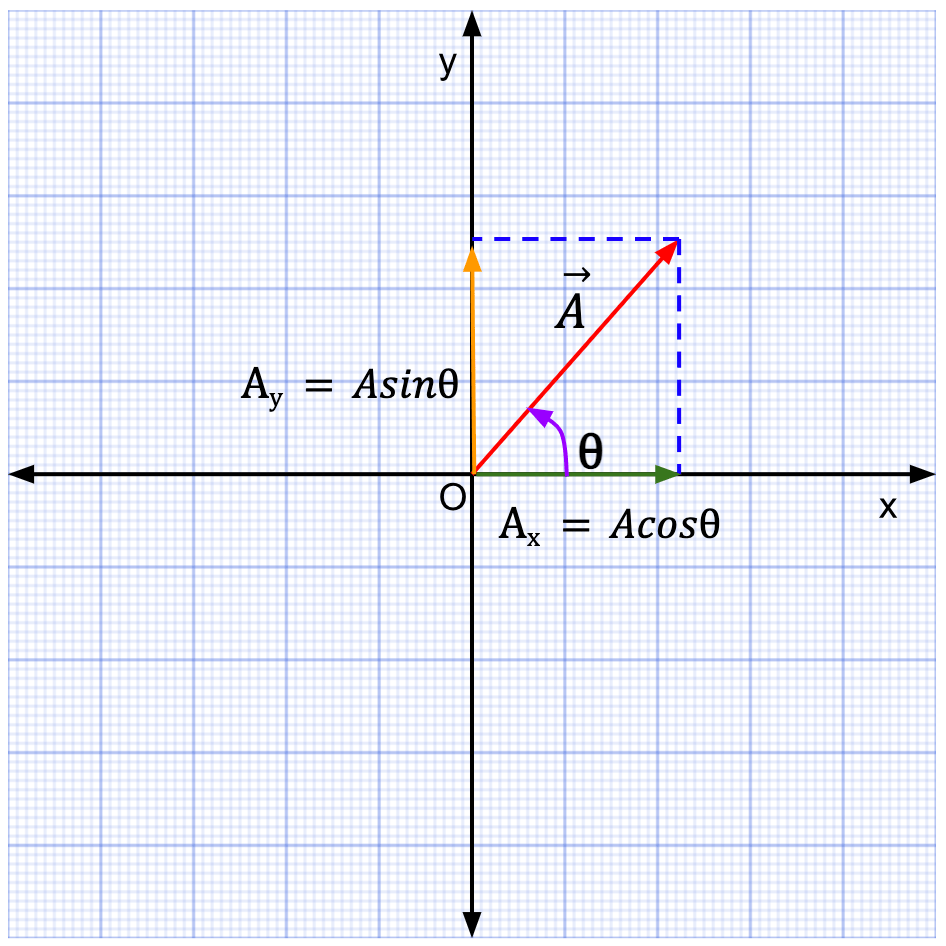

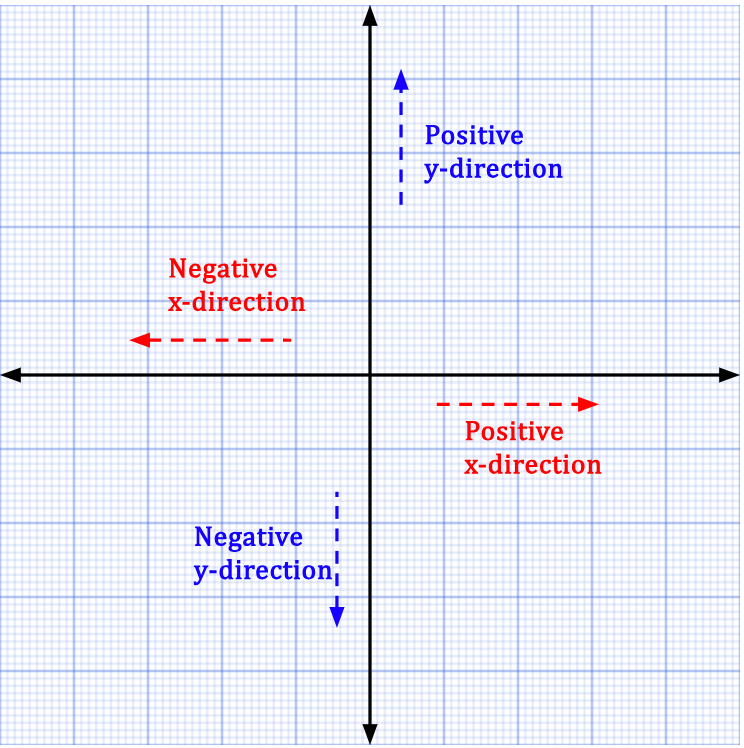

Figure 11: On the 2D cartesian coordinate system9,  can be broken down into two components, Ax and Ay. Ax is the component along the x-axis and tells you how much of

can be broken down into two components, Ax and Ay. Ax is the component along the x-axis and tells you how much of  lies along the x-direction. Ay is the component along the y-axis and tells you how much of

lies along the x-direction. Ay is the component along the y-axis and tells you how much of  lies in the y-direction (See Error #2).

lies in the y-direction (See Error #2).

In the cartesian coordinate system, a vector makes an angle with respect to some reference direction, usually taken to be the positive x-axis. In Figure 11,  makes an angle

makes an angle ![]() with the positive x-direction.

with the positive x-direction.

The components of a vector can be calculated from the magnitude of  and the angle it makes with the reference direction, in this case, positive x-axis, which is given by

and the angle it makes with the reference direction, in this case, positive x-axis, which is given by ![]() .

.

The Angle

It is important to note the properties of the angle in consideration, ![]() .

.

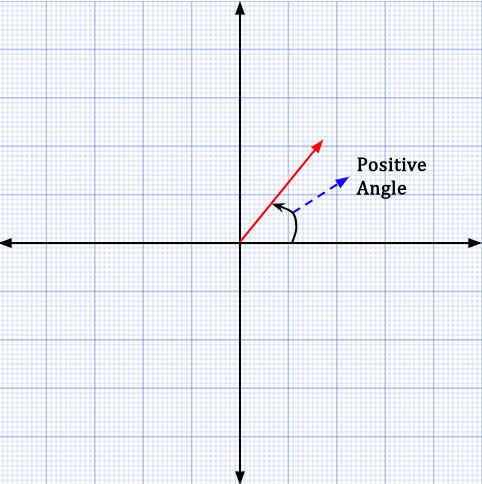

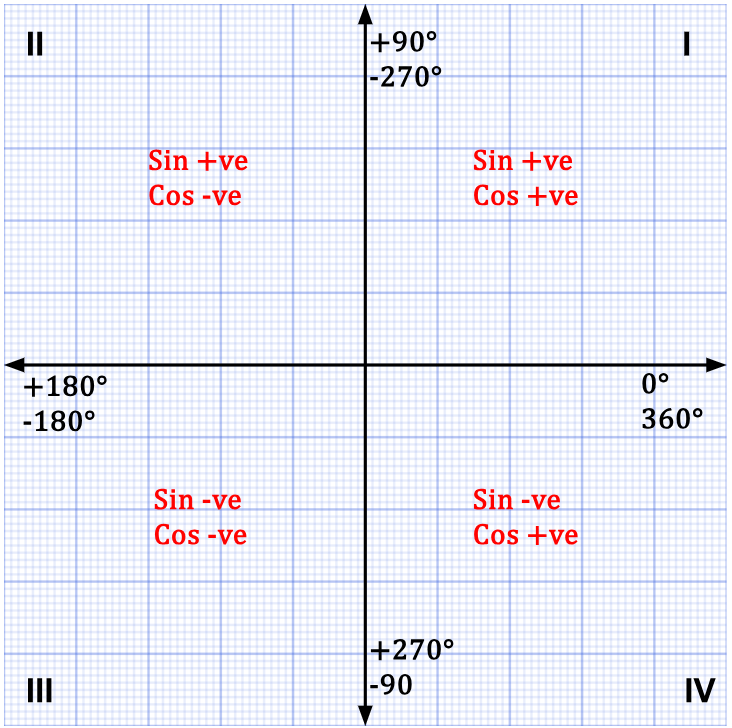

is positive for counter-clockwise angles, i.e., starting at positive x-axis and going towards positive y-axis.

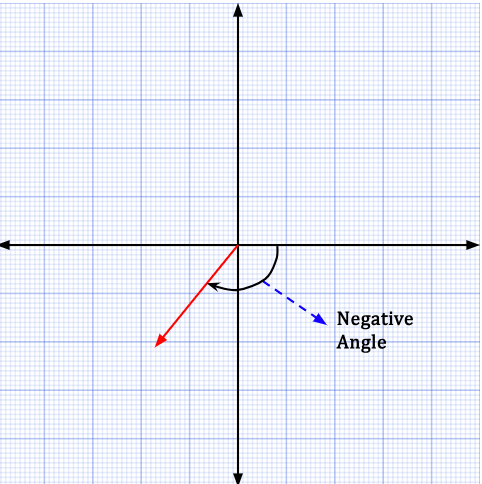

is positive for counter-clockwise angles, i.e., starting at positive x-axis and going towards positive y-axis. is negative for clockwise angles, i.e., starting at positive x-axis and going towards negative x-axis.

is negative for clockwise angles, i.e., starting at positive x-axis and going towards negative x-axis.

The Angle ![]() in Four Quadrants

in Four Quadrants

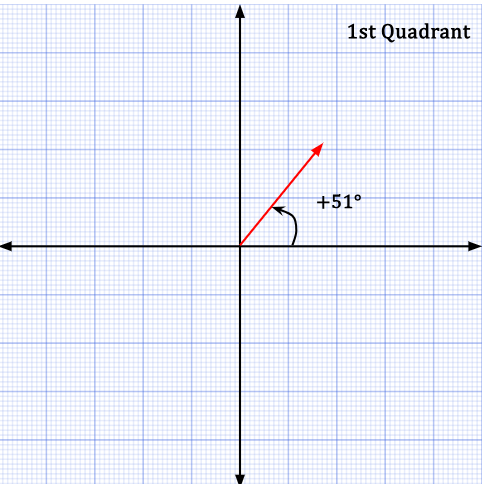

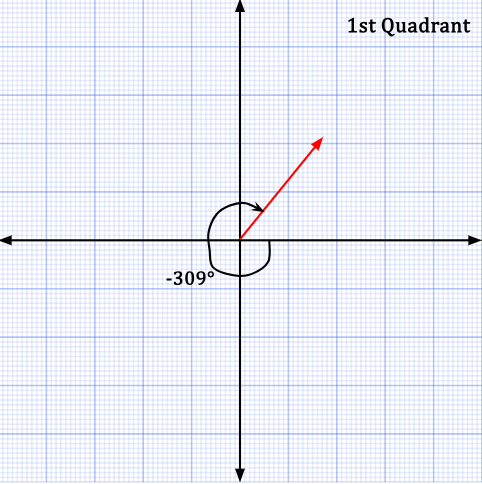

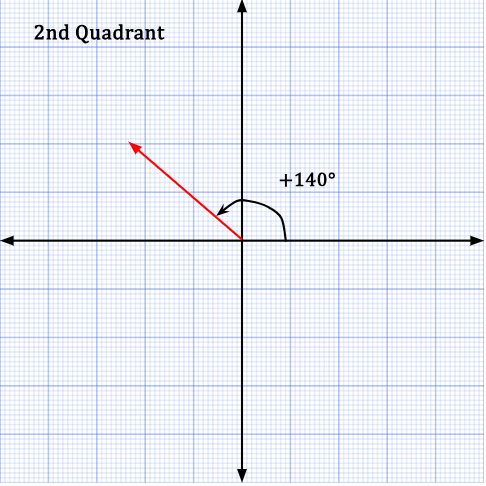

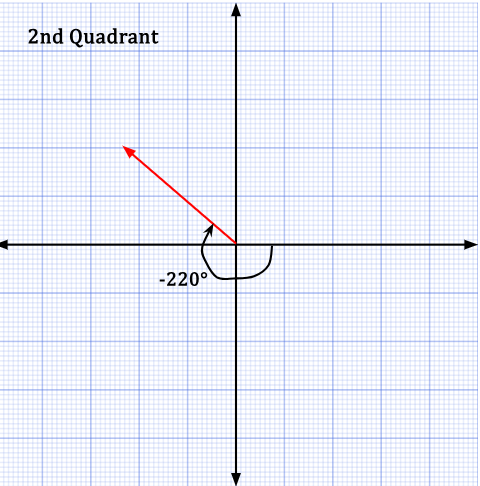

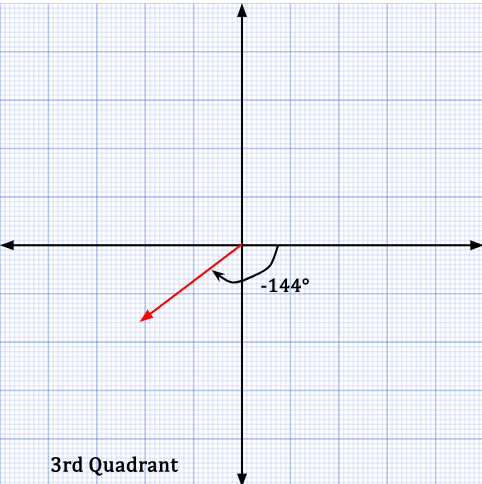

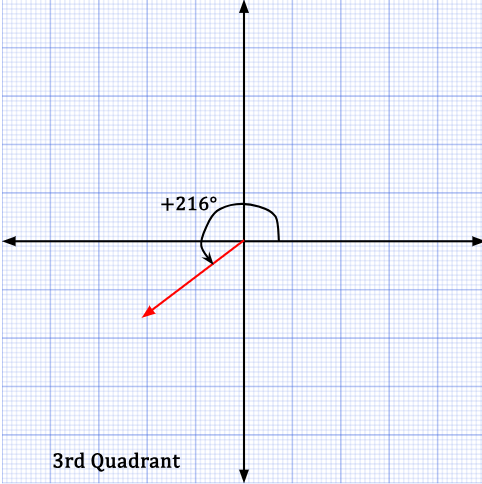

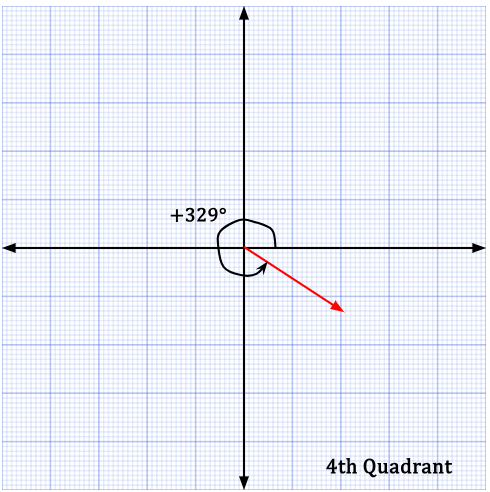

The angle that the vector makes with the reference direction can be measured in the counter-clockwise direction or clockwise direction. An angle measured in the counter-clockwise direction will yield a positive result while an angle measured in the clockwise direction will yield a negative result.

In the first quadrant, +51° can also be stated as -309°.

In the second quadrant, +140° can also be stated as -220°.

In the third quadrant, -144° can also be stated as +216°.

In the fourth quadrant, -31° can also be stated as +329°.

With the magnitude of  and angle

and angle ![]() known, the components can be easily determined by applying Pythagoras theorem to Figure 11:

known, the components can be easily determined by applying Pythagoras theorem to Figure 11:

cos![]() = Ax/

= Ax/ and sin

and sin![]() = Ay/

= Ay/ …..(7)

…..(7)

Ax =  cos

cos![]() and Ay =

and Ay =  sin

sin![]() 10……(8)

10……(8)

Figure 22: In the first quadrant, sin and cos are both positive. In equation (8), magnitude of  is a scalar quantity and hence, it will always be positive. If cos

is a scalar quantity and hence, it will always be positive. If cos![]() and sin

and sin![]() are both positive, this means that Ax and Ay will also be positive for a vector located anywhere in the first quadrant. Similarly, for the other three quadrants, refer to the table below.

are both positive, this means that Ax and Ay will also be positive for a vector located anywhere in the first quadrant. Similarly, for the other three quadrants, refer to the table below.

| Quadrant | Sin and Cos | Ax and Ay |

| I (0°< | Cos = +ve Sin = +ve | Ax = +ve Ay = +ve |

| II(90°< | Cos = -ve Sin = +ve | Ax = -ve Ay = +ve |

| III(180°< | Cos = -ve Sin = -ve | Ax = -ve Ay = -ve |

| IV(270°< | Cos = +ve Sin = -ve | Ax = +ve Ay = -ve |

Special Cases:

| Angle | Sin and Cos | Ax and Ay |

| Cos = +ve Sin = 0 | Ax = +ve Ay = 0 | |

| Cos = 0 Sin = +ve | Ax = 0 Ay = +ve | |

| Cos = -ve Sin = 0 | Ax = -ve Ay = 0 | |

| Cos = 0 Sin = -ve | Ax = 0 Ay = -ve |

How can you use Components to perform Vector Calculations?

Finding Magnitude and Direction

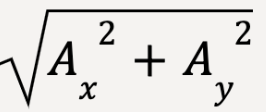

Components of a vector can be used to calculate the vector’s magnitude and direction. Given Ax and Ay, the magnitude of  is given by applying the Pythagorean theorem11:

is given by applying the Pythagorean theorem11:

=

=  …..(9)

…..(9)

The direction of  , given by

, given by ![]() (measured from positive x-axis and towards positive y-axis), is calculated as follows (See Error#3):

(measured from positive x-axis and towards positive y-axis), is calculated as follows (See Error#3):

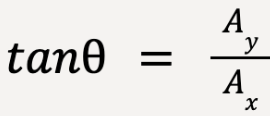

……(10)

……(10)

…….(11)

…….(11)

Note: Equations 9, 10 and 11 are applicable only if x and y axes are perpendicular to each other.

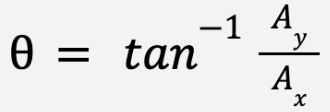

Multiply a vector by a scalar

When a vector is multiplied by a scalar as shown in equation 6,

= k

= k

Each component of  is k times the corresponding component of

is k times the corresponding component of  ,

,

Bx = kAx and By = kAy

Proof:

which is true as discussed earlier.

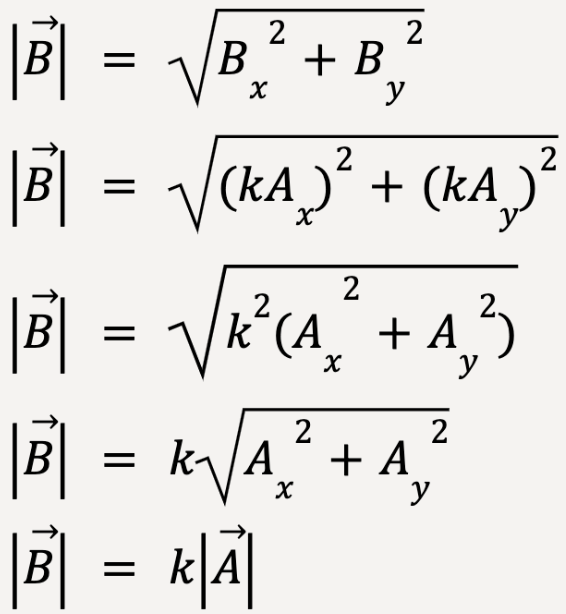

Vector Sum

For a given vector sum,  =

=  +

+  +

+ +

+ ,

,

where  ,

,  ,

, &

& are n-dimensional vectors;

are n-dimensional vectors;

Rx = Ax + Bx + Cx + Dx

Ry = Ay + By + Cy + Dy

Rz = Az + Bz + Cz + Dz

and so on, such that,

Rn = An + Bn +Cn +Dn….(12)

This method can be replicated for a sum of N-vectors, in which case,

Rx = Ax + Bx + Cx + Dx + Ex………………..+ Nx

Ry = Ay + By + Cy + Dy + Ey………………..+ Ny

Rz = Az + Bz + Cz + Dz + Ez………………..+ Nz

and so on, such that,

Rn = An + Bn +Cn +Dn + En………………..+ Nn….(13)

Vector sum using components can be easily visualized in 2D Cartesian coordinate system.

Unit Vectors

A unit vector is defined as a unitless13 quantity with a magnitude that equals one and it points towards a certain direction.

Unit Vector Notation: î (letter with a hat/caret on top)

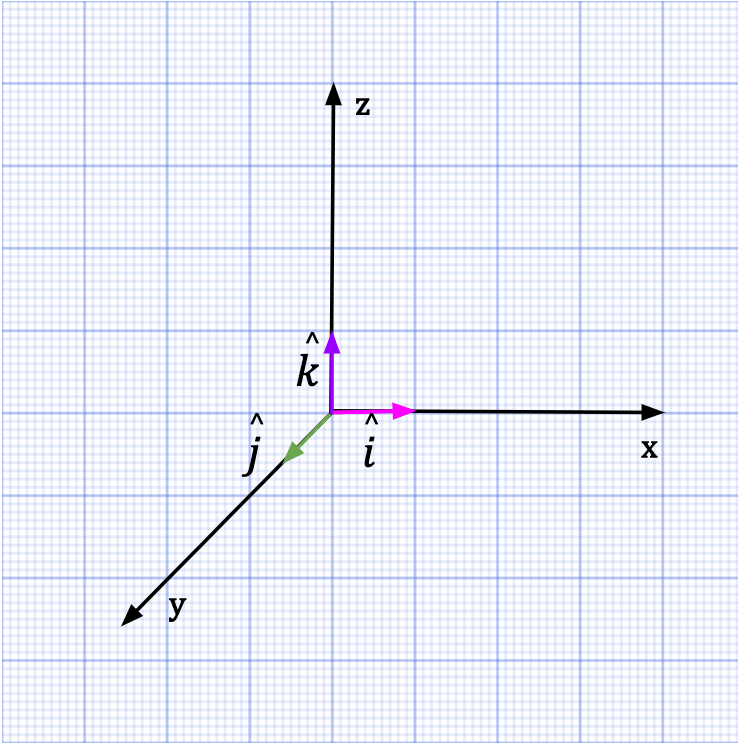

Figure 24: In the cartesian coordinate system, a unit vector (magnitude = 1) that points towards the x-axis is described by ![]() . Similarly, a unit vector (magnitude=1) that points towards the y-axis is denoted by

. Similarly, a unit vector (magnitude=1) that points towards the y-axis is denoted by ![]() , and if instead, it points towards the z-axis, it is denoted by

, and if instead, it points towards the z-axis, it is denoted by ![]() .

.

Vectors can then be expressed using components and unit vector notations.

= Ax

= Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]()

= Bx

= Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]()

Vector sum is then given by:

=

=  +

+

= Ax

= Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]() + Bx

+ Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]()

= (Ax + Bx)

= (Ax + Bx)![]() + (Ay + By)

+ (Ay + By) ![]() + (Az + Bz)

+ (Az + Bz)![]() ……(14)

……(14)

= Rx

= Rx![]() + Ry

+ Ry ![]() + Rz

+ Rz![]() ……..(15)

……..(15)

Notice in equation 14 that x components of the two vectors can be grouped together and subsequently added. The same can be done for y and z components of the two vectors. Once added, the final values are equivalent to x, y and z component of the resultant vector (equation 15).

Product of Vectors

Scalar Product

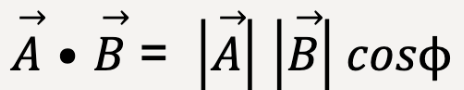

Scalar product is also called dot product because it is represented using the following notation:

It is called a scalar product because  and

and  are vectors but

are vectors but  is a scalar quantity.

is a scalar quantity.

Scalar product can be calculated using two methods.

Method 1:

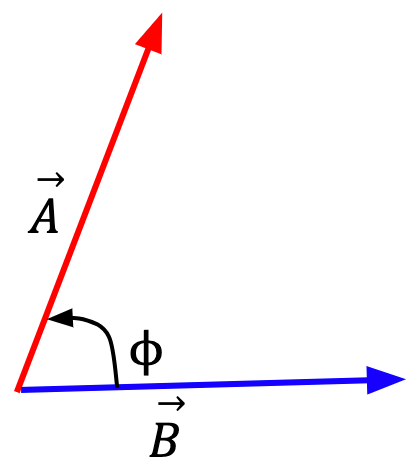

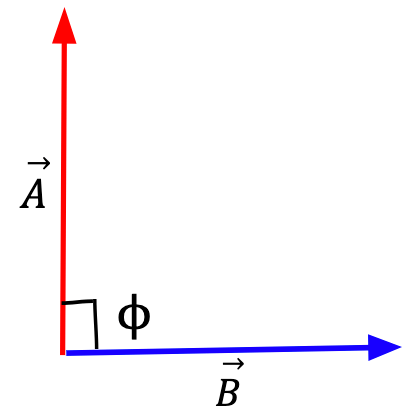

and

and  placed tail to tail with an angle

placed tail to tail with an angle  between them

between them …….(16)

…….(16)

Take two vectors, in this case  and

and  , such that they are placed tail to tail and the angle between them, denoted by

, such that they are placed tail to tail and the angle between them, denoted by  , lies between 0° and 180°. Dot product of these two vectors is then equal to the magnitude of

, lies between 0° and 180°. Dot product of these two vectors is then equal to the magnitude of  multiplied by the projection of

multiplied by the projection of  onto

onto  . Alternatively, it is equal to the magnitude of

. Alternatively, it is equal to the magnitude of  multiplied by the projection of

multiplied by the projection of  onto

onto  .

.

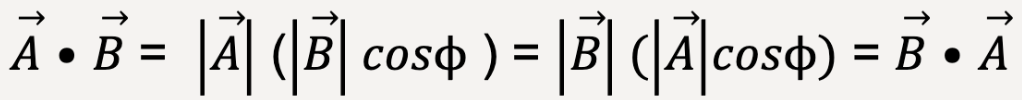

……(17)

……(17)

Thus, scalar product is commutative, because  .

.

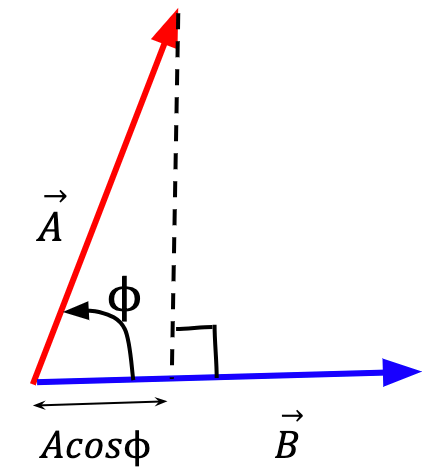

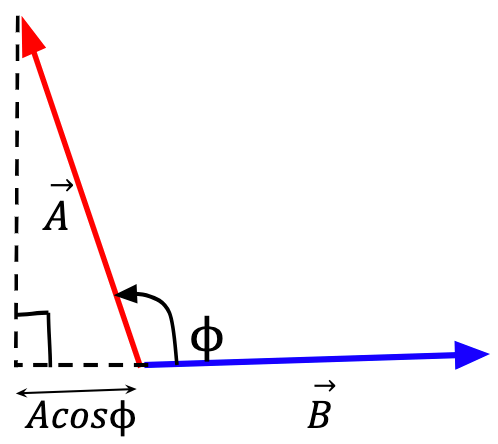

Projection of a Vector

A vector can be projected onto a certain direction.

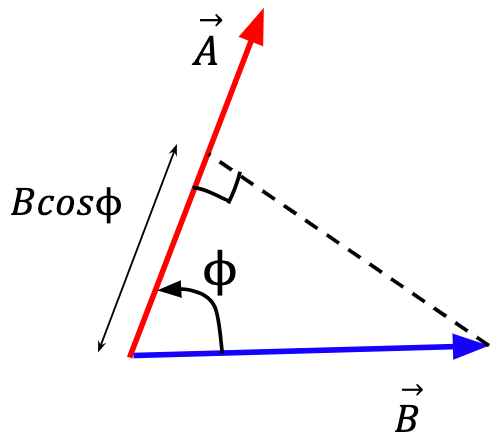

Figure 26: Projection of  onto

onto  is the component of

is the component of  in the direction of

in the direction of  and is equal to the magnitude of

and is equal to the magnitude of  times the cosine of the angle

times the cosine of the angle  .

.

Alternatively,

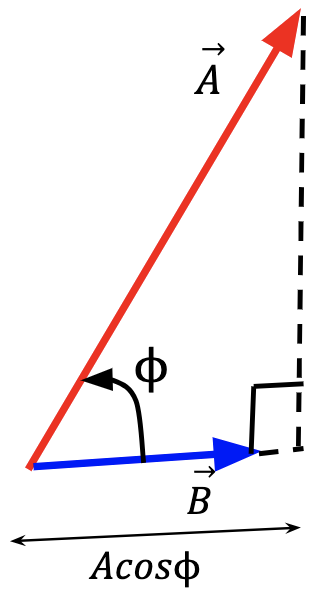

Figure 27: Projection of  onto

onto  is the component of

is the component of  in the direction of

in the direction of  and is equal to the magnitude of

and is equal to the magnitude of  times the cosine of the angle

times the cosine of the angle  .

.

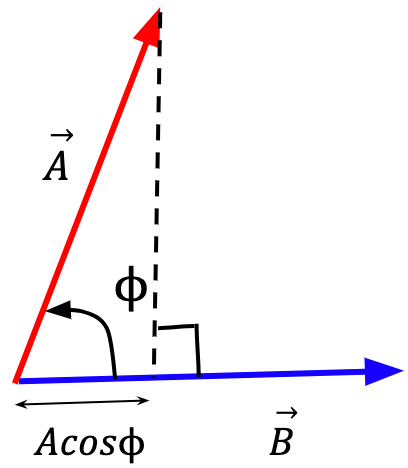

Note:

Figure 28: The projection of a vector is given by the shortest distance from one vector onto the other. The shortest distance is equivalent to a line drawn from first vector,  , onto the second,

, onto the second, , such that it makes a right angle with the second vector14. The projection of a vector can then extend beyond the length of the second vector as shown,

, such that it makes a right angle with the second vector14. The projection of a vector can then extend beyond the length of the second vector as shown,  .

.

The Angle

As stated earlier,  can range between 0° and 180°.

can range between 0° and 180°.

0°<

<90°,

<90°, cos

is +ve,

is +ve, Acos

is +ve,

is +ve, is +ve.

is +ve.

= 90°,

= 90°, cos

= 0,

= 0, Acos

= 0,

= 0,  = 0.

= 0.

90°<

<180°,

<180°, cos

is -ve,

is -ve, Acos

is -ve,

is -ve,  is -ve.

is -ve.Important: The dot product of two perpendicular vectors is always equal to zero.

Method 2:

Scalar product can also be computed using vector components. For two given vectors,

= Ax

= Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]()

= Bx

= Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]()

= (Ax

= (Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]() ) • (Bx

) • (Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]() )

)

= AxBx(

= AxBx(![]() •

•![]() ) + AxBy(

) + AxBy(![]() •

•![]() ) + AxBz(

) + AxBz(![]() •

•![]() ) + AyBx(

) + AyBx(![]() •

•![]() ) + AyBy(

) + AyBy(![]() •

•![]() ) + AyBz(

) + AyBz(![]() •

•![]() ) + AzBx(

) + AzBx(![]() •

•![]() ) + AzBy(

) + AzBy(![]() •

•![]() ) + AzBz(

) + AzBz(![]() •

•![]() )……(18)

)……(18)

Using equation 16,

![]() •

•![]() =

= ![]() •

•![]() =

= ![]() •

•![]() = (1)(1)(cos0°) = 1

= (1)(1)(cos0°) = 1

![]() •

•![]() =

= ![]() •

•![]() =

=![]() •

•![]() =

=![]() •

•![]() =

=![]() •

•![]() =

=![]() •

•![]() =(1)(1)(cos90°) = 0

=(1)(1)(cos90°) = 0

Substituting in equation 18,

= AxBx + AyBy + AzBz……(19)

= AxBx + AyBy + AzBz……(19)

The dot product of two vectors,  and

and  , is equal to the sum of the product of their components in a given direction.

, is equal to the sum of the product of their components in a given direction.

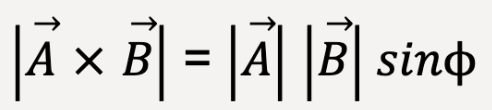

Vector Product

Vector product is also called cross product because it is represented using the following notation:

It is called a vector product because the result of  is a vector quantity.

is a vector quantity.

Vector product can be calculated using two methods.

Method 1:

and

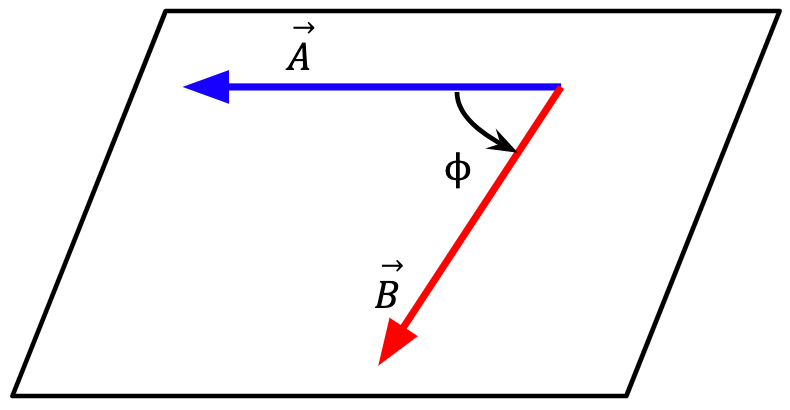

and  lie in a plane.

lie in a plane.Let two vectors, say  and

and  lie in a plane with an angle

lie in a plane with an angle  between them. The magnitude of the cross product between these two vectors can be calculated as follows:

between them. The magnitude of the cross product between these two vectors can be calculated as follows:

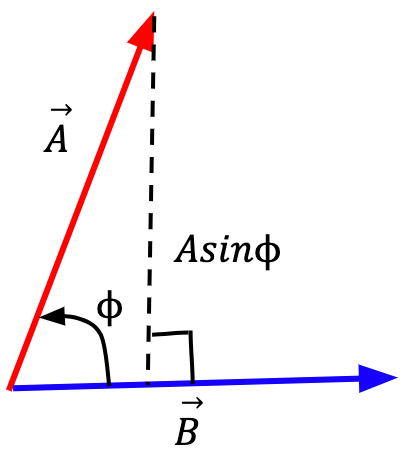

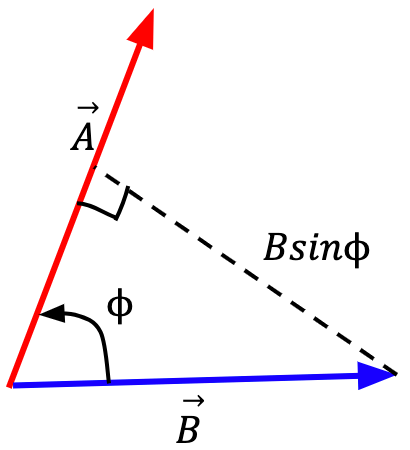

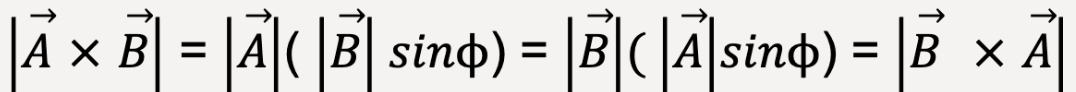

…..(20)

…..(20)

The magnitude of the cross product is equal to the magnitude of  multiplied by the component of

multiplied by the component of  perpendicular to

perpendicular to  . Alternatively, the magnitude of cross product is equal to the magnitude of

. Alternatively, the magnitude of cross product is equal to the magnitude of  multiplied by the component of

multiplied by the component of  perpendicular to

perpendicular to  .

.

perpendicular to

perpendicular to  = Asin

= Asin .

.

perpendicular to

perpendicular to  = Bsin

= Bsin .

.The magnitude of a cross product is commutative;

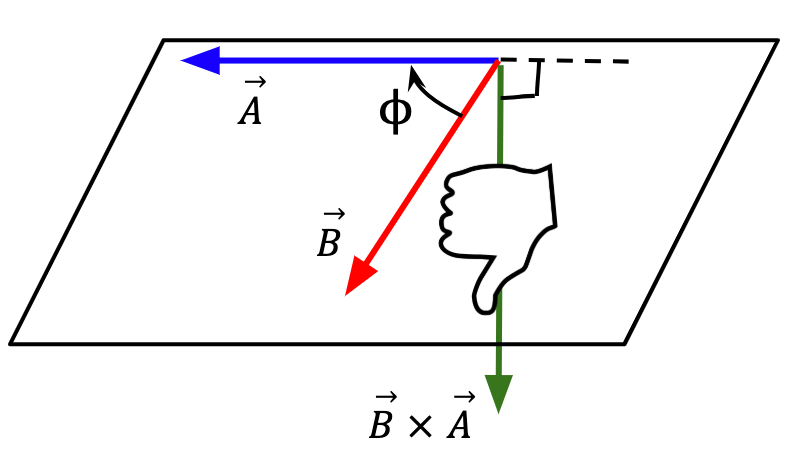

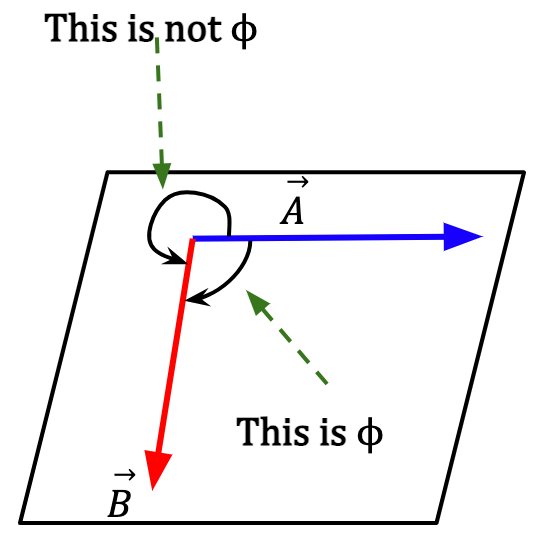

The direction of  is given by the right-hand rule and is always perpendicular to the plane in which the two vectors lie. If

is given by the right-hand rule and is always perpendicular to the plane in which the two vectors lie. If  and

and  lie along x and y axes respectively, then

lie along x and y axes respectively, then  will lie along the z-axis. The right-hand rule tells you whether the direction is along the positive z-axis or negative z-axis. Place your hand in the direction of the first vector (as shown in figure 35), in this case

will lie along the z-axis. The right-hand rule tells you whether the direction is along the positive z-axis or negative z-axis. Place your hand in the direction of the first vector (as shown in figure 35), in this case  , and curl your fingers towards the second vector, in this case

, and curl your fingers towards the second vector, in this case  . The thumb will point in the direction of

. The thumb will point in the direction of  . Notice that for

. Notice that for  , when you place your hand along

, when you place your hand along  and curl your fingers towards

and curl your fingers towards  , the thumb points in the opposite direction. This means that

, the thumb points in the opposite direction. This means that  and

and  are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Thus, vector product is anticommutative;

are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Thus, vector product is anticommutative;  = –

= – .

.

The Angle

Figure 34: and

and  vectors lie tail to tail in a plane and the angle

vectors lie tail to tail in a plane and the angle  is taken to be smaller of the two possible angles between them. This ensures that sin

is taken to be smaller of the two possible angles between them. This ensures that sin is positive (0°<

is positive (0°<  <180°) and hence, the magnitude of

<180°) and hence, the magnitude of  is positive. Magnitude of a vector is always greater than zero, i.e., always positive.

is positive. Magnitude of a vector is always greater than zero, i.e., always positive.

Special Case:

If  = 0° or 180°, sin

= 0° or 180°, sin is equal to zero and therefore,

is equal to zero and therefore,  is also zero. In other words, cross product between two parallel or antiparallel vectors is always zero. Consequently, cross product of a vector with itself is always zero.

is also zero. In other words, cross product between two parallel or antiparallel vectors is always zero. Consequently, cross product of a vector with itself is always zero.

Method 2:

Cross product can also be computed using vector components. For two given vectors,

= Ax

= Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]()

= Bx

= Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]()

= (Ax

= (Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]() )

) ![]() (Bx

(Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]() )

)

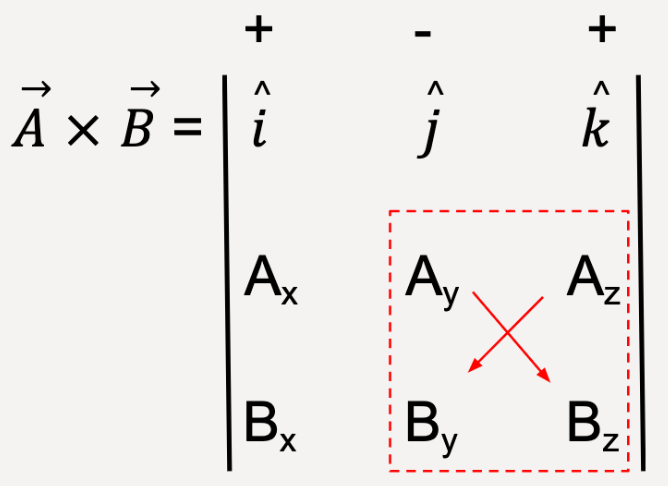

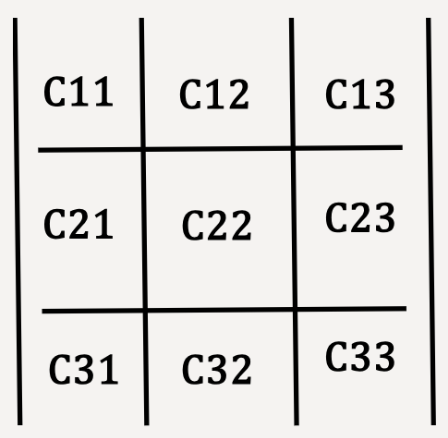

Cross products can be easily carried out using matrices, especially for vectors in 3D.

Draw a matrix with unit vectors in the first row, components of  in the second row and components of

in the second row and components of  in the third row. At the top of the unit vectors, start with the positive sign and subsequently alternate the sign between positive and negative, i.e., +, -, +, -, +, -, and so on. The second matrix provides labels for the each position in a 3×3 matrix. The general rule for matrix multiplication is as follows: Start with the first sign (+) and hold the value at C11 constant while the rest of the values in the first row and first column are ignored, in this case, C12, C13, C21 and C31. Next, the remaining four values are cross multiplied, such that C22 is multiplied by C33 and C23 is multiplied by C32 making sure a negative sign is added to the result of the latter multiplication. These steps are repeated for values at C12 and C13. For C12, make sure you start with the sign on top which would be a negative.

in the third row. At the top of the unit vectors, start with the positive sign and subsequently alternate the sign between positive and negative, i.e., +, -, +, -, +, -, and so on. The second matrix provides labels for the each position in a 3×3 matrix. The general rule for matrix multiplication is as follows: Start with the first sign (+) and hold the value at C11 constant while the rest of the values in the first row and first column are ignored, in this case, C12, C13, C21 and C31. Next, the remaining four values are cross multiplied, such that C22 is multiplied by C33 and C23 is multiplied by C32 making sure a negative sign is added to the result of the latter multiplication. These steps are repeated for values at C12 and C13. For C12, make sure you start with the sign on top which would be a negative.

Applying these steps to  matrix:

matrix:

= +

= +![]() (AyBz – AzBy) –

(AyBz – AzBy) – ![]() (AxBz – AzBx) +

(AxBz – AzBx) + ![]() (AxBy – AyBx), which can also be written as;

(AxBy – AyBx), which can also be written as;

= +

= +![]() (AyBz – AzBy) +

(AyBz – AzBy) +![]() (AzBx – AxBz ) +

(AzBx – AxBz ) + ![]() (AxBy – AyBx)…..(21)

(AxBy – AyBx)…..(21)

If the cross product between  and

and  is equal to

is equal to  , then the x-component of

, then the x-component of  , Cx = AyBz – AzBy; the y-component of

, Cx = AyBz – AzBy; the y-component of  , Cy = AzBx – AxBz; and the z-component of

, Cy = AzBx – AxBz; and the z-component of  , Cz = AxBy – AyBx.

, Cz = AxBy – AyBx.

Alternatively,

= (Ax

= (Ax![]() + Ay

+ Ay ![]() + Az

+ Az ![]() )

) ![]() (Bx

(Bx ![]() + By

+ By ![]() + Bz

+ Bz![]() )

)

= AxBx(

= AxBx(![]()

![]()

![]() )+ AxBy(

)+ AxBy(![]()

![]()

![]() ) + AxBz(

) + AxBz( ![]()

![]()

![]() )+ AyBx(

)+ AyBx( ![]()

![]()

![]() )+ AyBy (

)+ AyBy (![]()

![]()

![]() )+ AyBz(

)+ AyBz( ![]()

![]()

![]() )+ AzBx(

)+ AzBx(![]()

![]()

![]() ) + AzBy(

) + AzBy( ![]()

![]()

![]() ) + AzBz(

) + AzBz(![]()

![]()

![]() )……(22)

)……(22)

Using equation 20 and right-hand rule:

![]()

![]()

![]() =

=![]()

![]()

![]() =

=![]()

![]()

![]() = (1)(1)(sin0°) = 0

= (1)(1)(sin0°) = 0

![]()

![]()

![]() =

= ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]() = –

= –![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]() = –

= –![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]() =

= ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]() =

= ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]() = –

= – ![]()

Substituting these values into equation 22,

= AxBy(

= AxBy(![]() ) + AxBz( –

) + AxBz( –![]() )+ AyBx( –

)+ AyBx( –![]() )+ AyBz(

)+ AyBz( ![]() )+ AzBx(

)+ AzBx(![]() ) + AzBy( –

) + AzBy( – ![]() )

)

Bringing like terms together,

= AyBz(

= AyBz( ![]() ) + AzBy( –

) + AzBy( – ![]() ) + AxBz( –

) + AxBz( –![]() ) + AzBx(

) + AzBx(![]() ) + AxBy(

) + AxBy(![]() ) + AyBx( –

) + AyBx( –![]() )

)

= (AyBz – AzBy)

= (AyBz – AzBy)![]() + (AzBx – AxBz)

+ (AzBx – AxBz)![]() + (AxBy – AyBx)

+ (AxBy – AyBx)![]() ….(23)

….(23)

which is the same as equation 21.

Summary for Vector Addition

Vectors can be added in two ways:

- Using diagrams

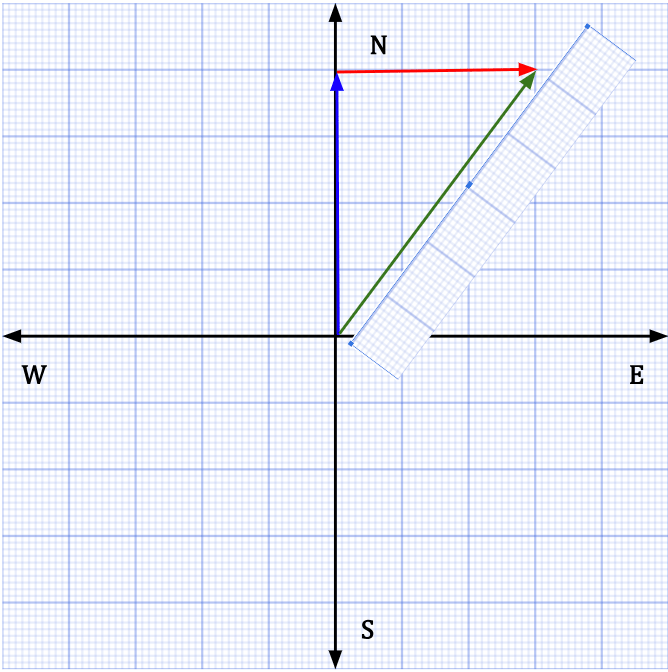

- Vectors can be added using diagrams but this method is not practical when dealing with vectors in three dimensions or more. For two vectors, scale diagrams can yield correct results. For example, you walk 400 km due North followed by 300 km due East. You can scale down 400 km to 4 units and 300 km to 3 units so that it can fit on a graph paper. In other words, the new values are scaled down by a factor of 100. When you measure the resultant displacement vector, it will be equal to 5 units which can be scaled up by 100 units yielding a displacement of 500 km (See Figure 36 below).

- Using vector components

- When components of vectors are given, they can be used to calculate the vector sum. The magnitude and direction of the resultant vector can be calculated using equations 9 and 10.

Common Errors in Understanding (Young et al., 2016)

Error #1:

When adding two vectors, such that,  =

=  +

+  , it is a common mistake to think that the magnitudes add as scalar quantities;

, it is a common mistake to think that the magnitudes add as scalar quantities;

=

=  +

+

This is wrong.  does not necessarily equal the sum of

does not necessarily equal the sum of  and

and  . Instead,

. Instead,  depends on

depends on  ,

,  and the angle between

and the angle between  and

and  . In a special case where

. In a special case where  and

and  parallel, magnitude of

parallel, magnitude of  does equal magnitude of

does equal magnitude of plus magnitude of

plus magnitude of  . However, if

. However, if  and

and  are antiparallel,

are antiparallel,  = |

= | –

–  |15.

|15.

Error #2:

Components of a vector are not vectors. They are signed scalars. If Ax is positive, it lies along the positive x-direction. If Ax is negative, it lies along the negative x-direction. Similarly, if Ay is positive, it lies along the positive y-direction, and if Ay is negative, it lies along the negative y-direction.

Error #3:

Any tangent value will yield two angles between 0° and 360°, for instance, tan![]() is -1 at

is -1 at ![]() = 135° and

= 135° and ![]() = 315°. Similarly, tan

= 315°. Similarly, tan![]() = 0.4244 for both

= 0.4244 for both ![]() = 23° and

= 23° and ![]() = 23° + 180° = 203°. In general, angles separated by 180° will have the same tangent value. How does one find out which angle is the correct choice? The correct value of

= 23° + 180° = 203°. In general, angles separated by 180° will have the same tangent value. How does one find out which angle is the correct choice? The correct value of ![]() can be identified by analyzing the given vector components. For tan

can be identified by analyzing the given vector components. For tan![]() = 0.4244, if Ax and Ay are both positive (1st quadrant), the correct value of

= 0.4244, if Ax and Ay are both positive (1st quadrant), the correct value of ![]() will be 23° and if Ax and Ay are both negative (3rd quadrant), the correct value of

will be 23° and if Ax and Ay are both negative (3rd quadrant), the correct value of ![]() will be 203°.

will be 203°.

Back to Magnitude and Direction

- Young, H.D. et al. (2016) Sears and Zemansky’s university physics: With modern physics. 14th edn. Boston: Pearson. ↩︎

- Definitions of SI base units (2020) NIST. Available at: https://www.nist.gov/si-redefinition/definitions-si-base-units (Accessed: 24 December 2024) ↩︎

- The adopted standards for different units have a long history, and have changed over time with newer standards being more precise. For example, until 2018, 1 kg was defined as the mass of a cylinder made of platinum-iridium alloy locked in a vault in Paris. ↩︎

- Both 2.85m and 158 km have 3 significant digits but the uncertainties are vastly different. ↩︎

- Zeroes to the left of non-zero digits do not count. ↩︎

- Zeroes after a decimal point are significant. ↩︎

- Numbers like 5900 should be stated using scientific notation, as 5.9×103 or 5.90×103 . This makes it easier to determine the uncertainty, for example, 5.9×103 has two significant digits and so the uncertainty is ~100 and 5.90×103 has three significant digits and the uncertainty is ~10. ↩︎

- Zeroes between non-zero numbers are significant. ↩︎

- 2D Cartesian coordinate system is described by an origin and two axes labelled x and y. The position of any point on the plane can then be given by two values, an x-coordinate, which tells you how far the point is from the origin along the x-axis, and a y-coordinate, which tells you far the point is from the origin along the y-axis. ↩︎

- For the equations to be valid,

must be measured counter-clockwise, i.e., from positive x-axis towards positive y-axis. If the angle is given from a different reference direction or is measured clockwise, first determine what the angle would be when you start at +x-axis and go towards +ve y-axis, then apply these equations to find the components. ↩︎

must be measured counter-clockwise, i.e., from positive x-axis towards positive y-axis. If the angle is given from a different reference direction or is measured clockwise, first determine what the angle would be when you start at +x-axis and go towards +ve y-axis, then apply these equations to find the components. ↩︎ - Disregard the negative root because magnitude is a scalar quantity. ↩︎

- Since

makes an angle,

makes an angle,  , with the reference direction (+ve x-axis) such that 90°<

, with the reference direction (+ve x-axis) such that 90°< <180°, this means that the x component of the vector, i.e., Bx, will be negative. ↩︎

<180°, this means that the x component of the vector, i.e., Bx, will be negative. ↩︎ - Unit vectors have no units. ↩︎

- The projection can be calculated by applying pythagorean theorem to this right angle triangle. ↩︎

- The difference in magnitudes is placed inside an absolute symbol because the magnitude of a vector is a scalar quantity which is always positive. ↩︎