List of Sources:

- Young et al., 20161

- Mezzotint print of oil painting, portrait of Isaac Newton, 1712 by Kneller, Sir Godfrey; Smith, John is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Graphs generated using Desmos

Table of Contents:

- Force and Interactions (Young et al., 2016)

- Newton’s First Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

- Newton’s Second Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

- Mass and Weight (Young et al., 2016)

- Newton’s Third Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

- Additional Topics (Young et al., 2016)

Newton’s Laws of Motion allow us to study the forces that cause a body to move in a certain fashion, also known as the study of dynamics (as discussed earlier, the study of the motion itself is referred to as kinematics).

Newton stated three laws of motion to describe the principles of dynamics.

- The First Law of Motion states that in the absence of a net force, a body’s motion does not change.

- The Second Law of Motion states that in presence of a net force, a body will accelerate.

- The Third Law of Motion describes the relationship between forces that two bodies exert on each other.

Force and Interactions (Young et al., 2016)

Force is an interaction between two bodies or between a body and its environment. It is a vector quantity, which means that it has both a magnitude and a direction. The SI unit of force is Newton (N).

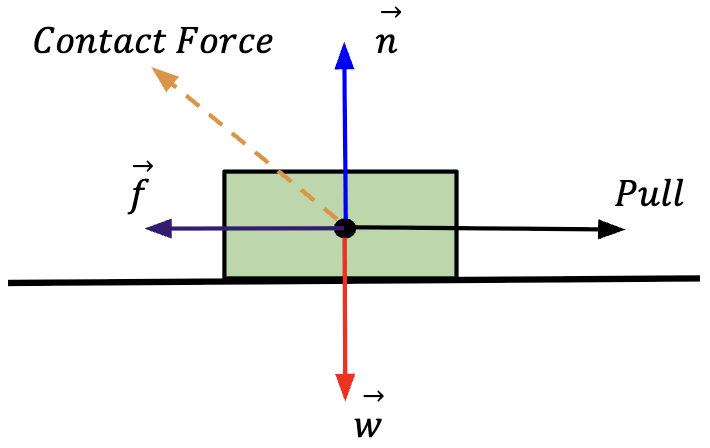

Contact Force

Contact force, as the name suggests, refers to direct force exerted on an object through the action of touch. For instance, if a person pushes on a block with his/her hand.

There are three kinds of contact forces:

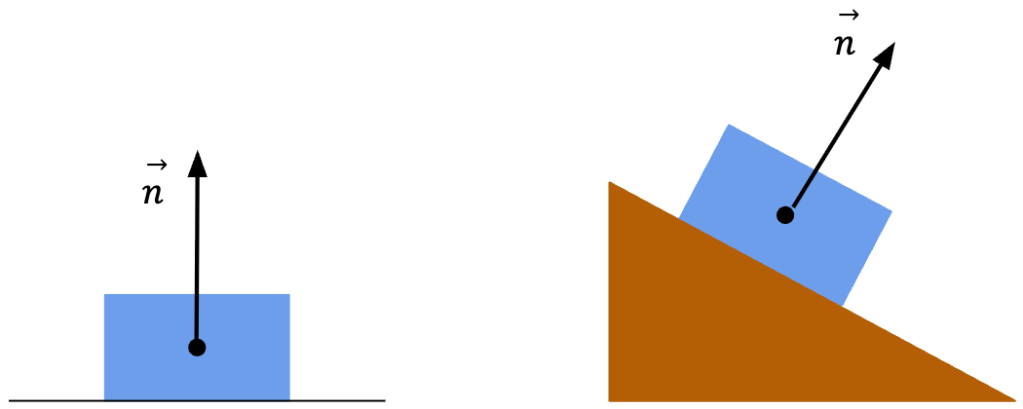

Normal Force

Force which is exerted on an object by the surface it is in contact with. It is called ‘normal’ force because the force applied is always perpendicular to the surface that exerts it.

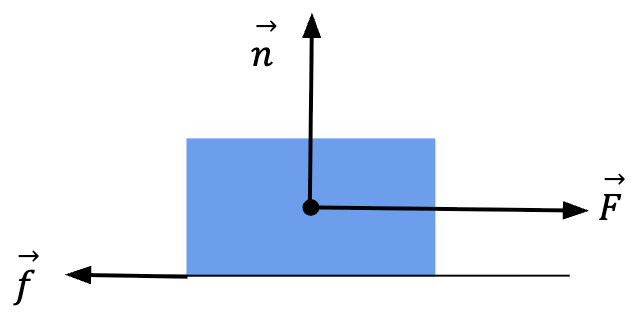

Friction Force

Like normal force, friction force is also exerted by the surface on which the object sits. However, contrary to the perpendicular nature of normal force, friction force acts parallel to the surface that exerts it such that it will oppose relative motion between the object and the surface.

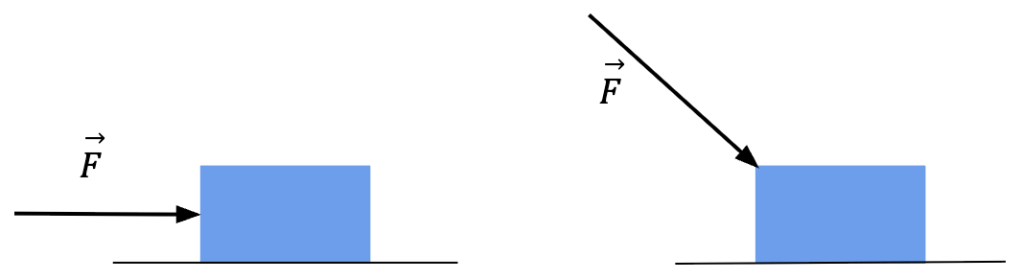

is applied to a block, the surface exerts friction force,

is applied to a block, the surface exerts friction force,  which opposes the motion.

which opposes the motion.  represents the normal force applied by the surface on the block.

represents the normal force applied by the surface on the block.Tension Force

Tension force is described as the pull exerted by a cord or a rope on the object it is connected to.

Long-Range Force

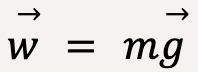

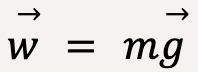

Long-range forces, as the name suggests, act even when there is no direct contact between two bodies. For instance, gravitational force or force between two magnets. Gravity acts on an object even when the object is separated from the Earth by empty space. This gravitational force that Earth exerts on surrounding objects is defined as weight and is given by;  , where m is the mass of the object and

, where m is the mass of the object and ![]() is the acceleration due to gravity, the magnitude of which is equal to 9.80 m/s2 and is always directed towards the Earth.

is the acceleration due to gravity, the magnitude of which is equal to 9.80 m/s2 and is always directed towards the Earth.

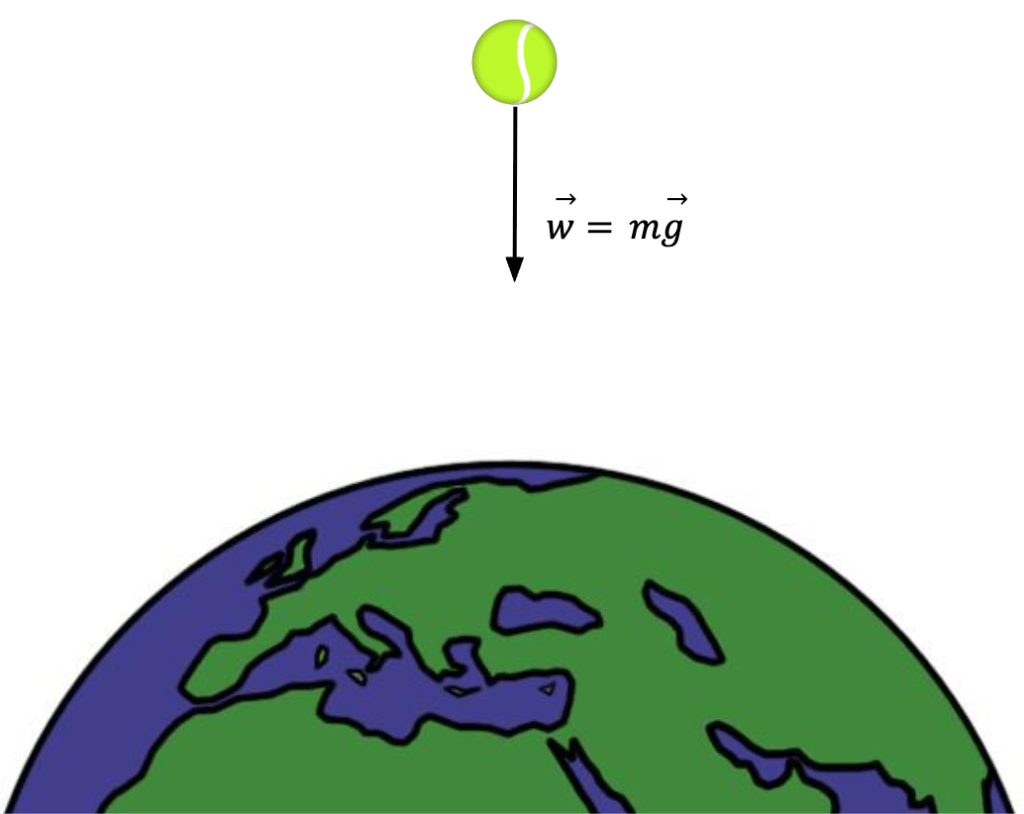

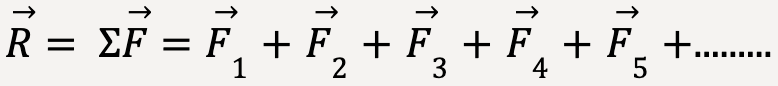

Superposition of Forces

The principle of superposition of forces states that if multiple forces act on a body, the resultant force is equal to the vector sum of all the applied forces. In other words, even though multiple forces are exerted on the body, it is as if a single force is being applied to the body which equals the vector sum of all the applied forces.

is equal to the vector sum of applied forces,

is equal to the vector sum of applied forces,  and

and  .

.The resultant force,  ;

;

…..(1)

…..(1)

In general,

……(2)

……(2)

The resultant force,  can be calculated using vector components of net force,

can be calculated using vector components of net force,  such that;

such that;

…..(3)

…..(3)

…..(4)

…..(4)

…..(5)

…..(5)

…..(6)

…..(6)

Newton’s First Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

A body in equilibrium will continue to move indefinitely with constant velocity.

- A body is said to be in equilibrium when the net force acting on it is equal to zero. If the net force is zero;

= 0, that means the components of net force in all directions are equal to zero; Σ Fx = ΣFy = ΣFz = 0. A net force of zero does not mean that there are no forces acting on the body. Even if there are forces acting on the body, they cancel each other out, or in other words, the vector sum of all the forces (principle of superposition) is zero and thus, the net force acting on the body is zero.

= 0, that means the components of net force in all directions are equal to zero; Σ Fx = ΣFy = ΣFz = 0. A net force of zero does not mean that there are no forces acting on the body. Even if there are forces acting on the body, they cancel each other out, or in other words, the vector sum of all the forces (principle of superposition) is zero and thus, the net force acting on the body is zero. - The body will move with a constant velocity which means that the magnitude and direction of velocity remain unchanged. In other words, it will move in a straight line with constant speed.

- It will move indefinitely unless an external force is applied opposite to the direction of motion which will bring the body to a stop. This tendency to continue to move once set in motion is called inertia. The tendency of a body at rest to remain at rest is also called inertia.

- An external force applied in the direction of motion will accelerate it, which means that the body will start to move with greater velocity.

Inertial Frames of Reference

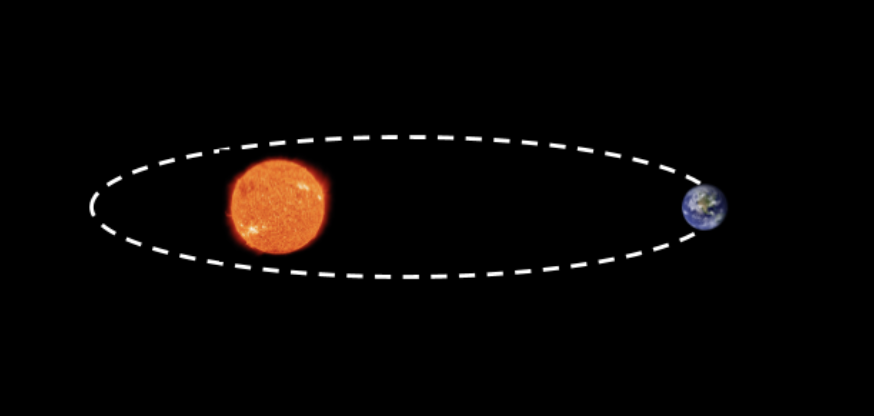

Note: Newton’s first law of motion is only applicable in inertial frames of reference. An accelerating frame is a non-inertial frame of reference. For example, when you are standing in a bus that is accelerating forward, you tend to move backwards. There is no net force acting on you and yet your velocity changes. You can conclude that Newton’s first law is not being followed in the bus, but it would be incorrect to assume so. Since the bus is accelerating, it is not an inertial frame of reference and Newton’s first law does not apply. Earth is considered an approximate inertial frame of reference. Earth is accelerating because of it’s rotation and revolution around the sun but these effects are negligible. Thus, Newton’s First Law is sometimes referred to as the Law of Inertia.

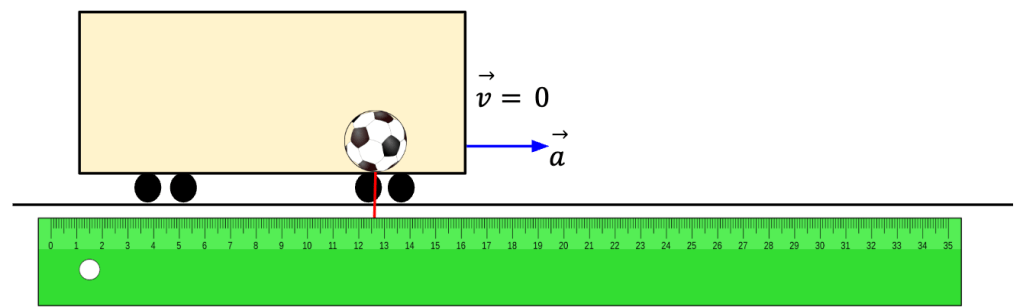

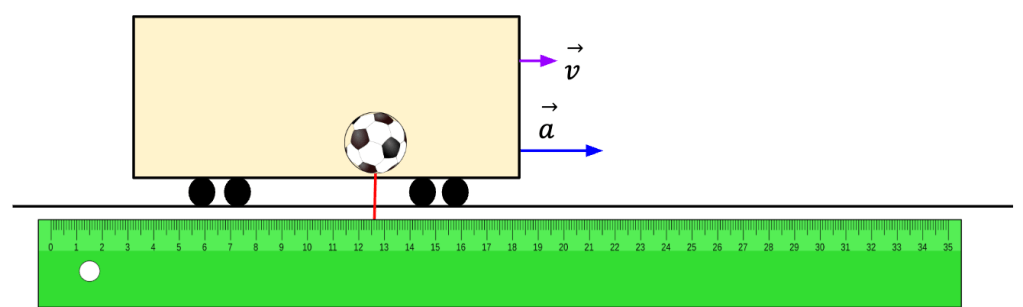

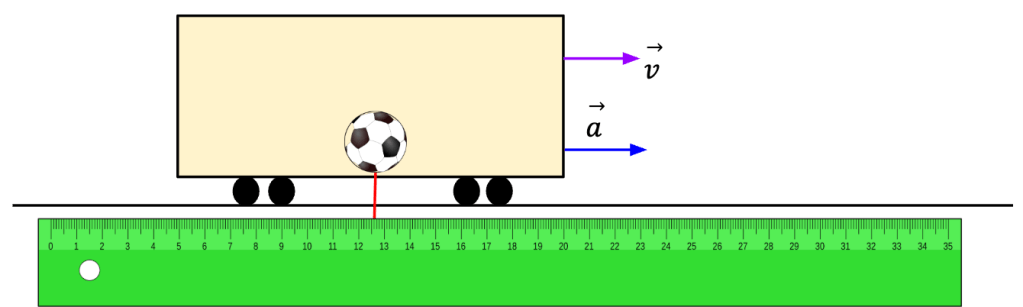

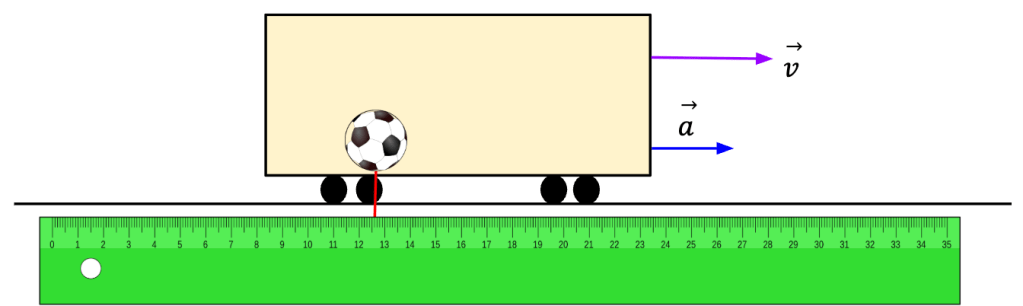

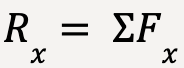

For example, let’s say a train starts accelerating forward and a soccer ball sitting on the train’s floor starts to roll backwards. A passenger in the train will incorrectly conclude that Newton’s first law is being violated because the ball starts to move even though there is no net force acting on it. However, such reasoning is wrong because train is an accelerating frame of reference in which Newton’s first law does not hold. However, to an observer on the side of the tracks, the ball continues to appear to be at rest (see below) because Earth is an approximate inertial frame of reference and with respect to the Earth, the ball remains at rest because there is no net force acting on it. Thus, in this frame, Newton’s law does hold.

Similarly, if the train starts to make a turn, to a passenger sitting in the train, the ball will appear to move sideways towards the outside of the turn. However, to an outside observer, the ball keeps moving in a straight line and thus, Newton’s first law will still hold.

Earth is not the only inertial frame of reference. If there is an inertial frame of reference, A and another frame of reference, B, such that it is moving at constant velocity,  , relative to A, then B will also be an inertial frame of reference. A body might move at different velocities in the two frames, but in both frames, it will move with a constant velocity, i.e., zero acceleration, meaning Newton’s first law will hold.

, relative to A, then B will also be an inertial frame of reference. A body might move at different velocities in the two frames, but in both frames, it will move with a constant velocity, i.e., zero acceleration, meaning Newton’s first law will hold.

Newton’s Second Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

Mass and Force

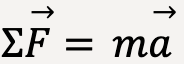

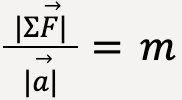

Experiments show that net force acting on a body is related to the acceleration of the body. First, a body will accelerate in the direction of the applied net force. Second, the strength of the applied net force is directly proportional to the magnitude of acceleration observed in the body. In other words, if net force is doubled, acceleration will double as well.

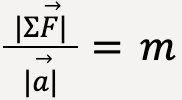

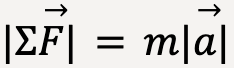

This implies that the ratio of the magnitude of net force,  to the magnitude of acceleration,

to the magnitude of acceleration,  is constant. This ratio is defined as the inertial mass or simply mass of the body, m.

is constant. This ratio is defined as the inertial mass or simply mass of the body, m.

…..(7)

…..(7)

or

…..(8)

…..(8)

Since mass and acceleration are inversely proportional, greater is a body’s mass, larger is its resistance to accelerate (or smaller is the acceleration).

The SI unit of mass is kilogram. A newton can be defined in terms of units of mass and acceleration, such that, a force of 1N accelerates a body of mass 1 kg by 1 m/s2.

…..(9)

…..(9)

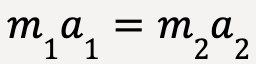

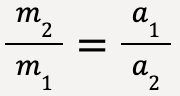

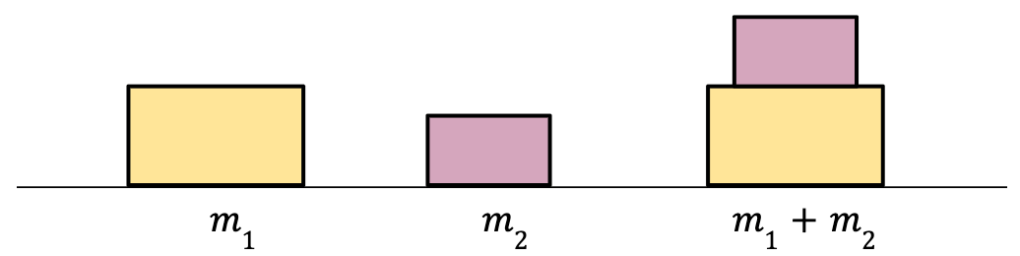

Furthermore, if the same amount of force is applied to two bodies of mass m1 and m2 such that the force produces an acceleration of a1 and a2 respectively, then using equation (8), we can say that:

…..(10)

…..(10)

…..(11)

…..(11)

When same amount of net force acts on two bodies, the ratio of their masses is equal to the inverse ratio of their acceleration.

Note: When two bodies of mass m1 and m2 are joined together, the total mass of this composite body is equal to m1+m22.

Newton’s Second Law

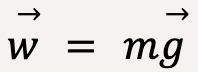

If a body is acted on by forces,  , the net force,

, the net force,  will cause the body to accelerate in the same direction in which the net force is acting, regardless of whether the path of motion is straight or curved.

will cause the body to accelerate in the same direction in which the net force is acting, regardless of whether the path of motion is straight or curved.

The net force is then given by;

…..(12)3

…..(12)3

where m equals the mass of the body and ![]() represents the acceleration.

represents the acceleration.

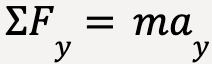

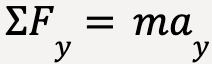

Equation (12) can be broken down into its component form:

…..(13)

…..(13)

…..(14)

…..(14)

…..(15)

…..(15)

Important:  only includes external forces, which means that forces that are acting on the body, not the force that the body exerts on others. A body cannot exert force on itself!

only includes external forces, which means that forces that are acting on the body, not the force that the body exerts on others. A body cannot exert force on itself!

Newton’s second law, like the first law, is only valid in inertial frames of reference.

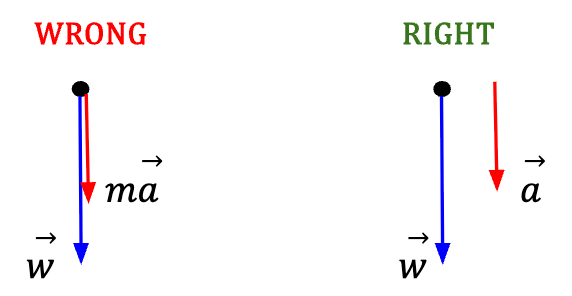

Common Error in Understanding

is not a force acting on the body. This means that acceleration is not caused by a force

is not a force acting on the body. This means that acceleration is not caused by a force  acting on the body but because the net force,

acting on the body but because the net force,  is nonzero.

is nonzero.

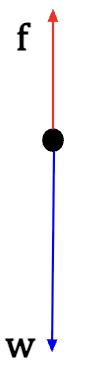

is not a force acting on the falling object. Free body diagram on the right is correct because the only force acting on a free falling body is the force of gravity or the body’s weight. A downward arrow can be drawn at a distance from the free body diagram to indicate the direction of acceleration.

is not a force acting on the falling object. Free body diagram on the right is correct because the only force acting on a free falling body is the force of gravity or the body’s weight. A downward arrow can be drawn at a distance from the free body diagram to indicate the direction of acceleration.In this case, Newton’s second law reads,

…..(16)

…..(16)

Note: The x and z components are irrelevant because the motion and net force are in the y-direction only.

Apparent Weight and Weightlessness

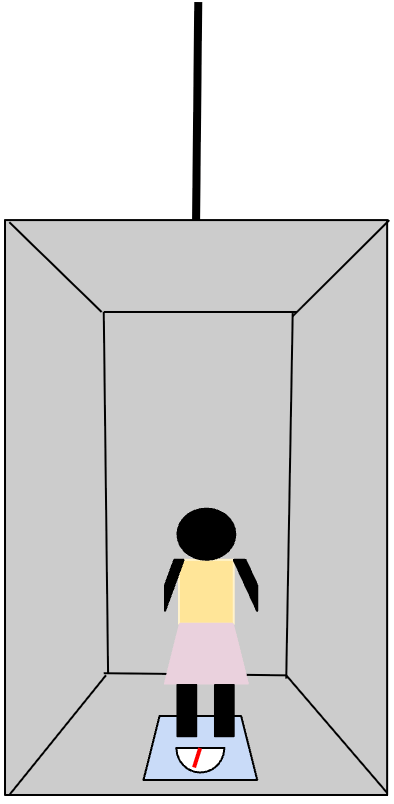

Let’s say a woman with mass m is standing on a bathroom scale while riding an elevator that is moving with an acceleration ay.

and her weight,

and her weight,  .

.When ay=0 which means that the elevator is at rest, the reading on the bathroom scale, n (normal force) will be equal to the woman’s weight given by w = mg. This is because according to Newton’s first law, since the body is in equilibrium, net force acting on it must be zero.

= 0…..(17)

= 0…..(17)

Taking upwards direction to be positive;

n – w = 0…..(18)

n = w…..(19)

For nonzero acceleration given by ay, we will need to use Newton’s second law whereby the net force acting on the body is not zero;

…..(20)

…..(20)

n – w = may…..(21)

n = m (ay + g)…..(22)

n is referred to as the apparent weight of the woman. This means that when the elevator is accelerating upwards and ay is positive, the reading on the scale (n) will be larger than the woman’s weight. On the other hand, if the elevator is accelerating downwards and ay is negative, the reading on the scale (n) will be smaller than the woman’s weight. This is the reason why you might feel your weight is changing when you ride an elevator!

For a body in free fall, say an apple falling from the tree or an astronaut in orbit around the Earth, ay = -g which means that n in equation 22 will be zero. This is why the astronaut will experience apparent weightlessness. It is important to understand that gravitational force is still acting on the astronaut (gravity does not become zero) and he does not really become weightless, he just feels as though he is weightless due to n being zero.

Mass and Weight (Young et al., 2016)

Mass and weight are commonly used interchangeably, which is wrong because they are entirely different quantities.

What is Mass?

Mass is an inertial property of a body as described by Newton’s second law of motion;

…..(23)

…..(23)

Larger is the mass, greater is the force required to accelerate the body. Mass is a scalar quantity and it’s SI unit is kilogram (kg).

What is Weight?

Weight4 is the force exerted by Earth’s gravitational pull on the body. Weight is a vector quantity and it’s SI unit is Newton (N).

Relationship between Mass and Weight

As discussed earlier;

…..(24)

…..(24)

Weight is directly proportional to the mass of the body. Larger is the mass of a body, greater is the force with which gravity pulls on it, in other words, greater is it’s weight.

For example, let’s say you have a block with large mass. It will be hard to push the block (hard to accelerate) because of its large mass, and it will be hard to lift the block because of it’s large weight.

The relationship,  provides a value of mass which is referred to as gravitational mass. Newton’s second law,

provides a value of mass which is referred to as gravitational mass. Newton’s second law,  gives a value of mass which is referred to as the inertial mass. Experiments have shown that the two values are identical5 (with insignificant variance).

gives a value of mass which is referred to as the inertial mass. Experiments have shown that the two values are identical5 (with insignificant variance).

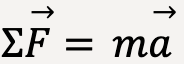

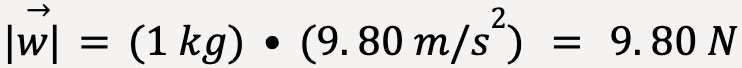

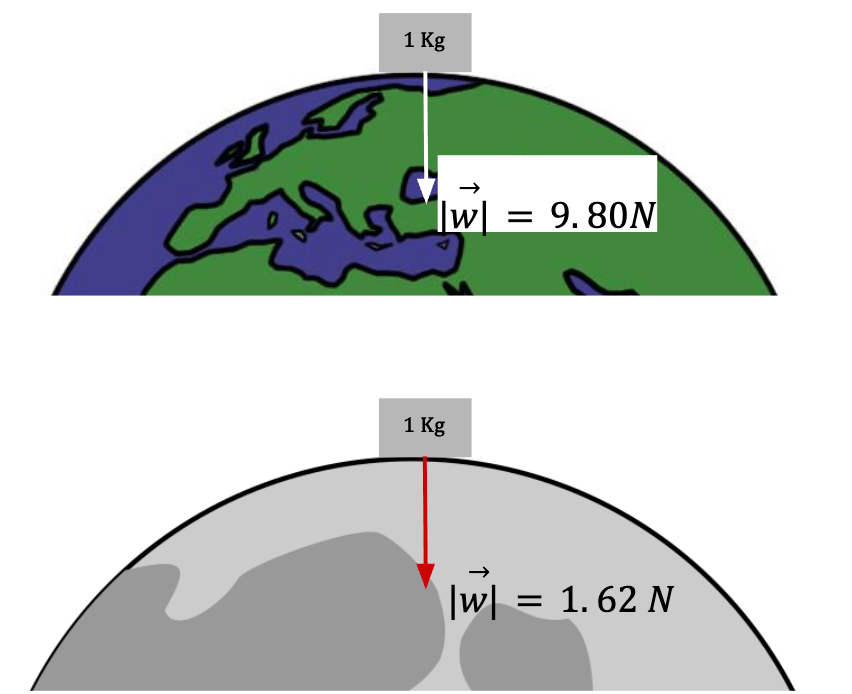

For an object of mass 1 kg, it’s weight will be;

…..(25)

…..(25)

Variation of g with Location

The value of g on Earth6 is approximately, g = 9.80 m/s2. At a different place, let’s say the moon, value of g = 1.62 m/s2. The value of g varies from place to place depending on the strength of gravitational pull.

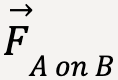

Newton’s Third Law of Motion (Young et al., 2016)

Forces come in pairs. If you push on a wall, the wall will push back on you.

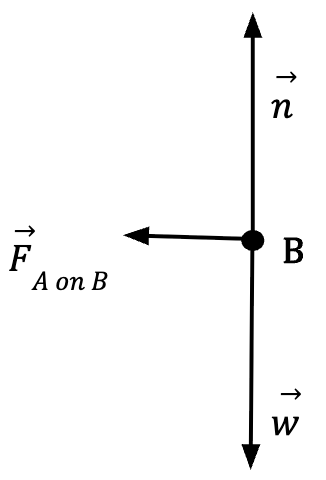

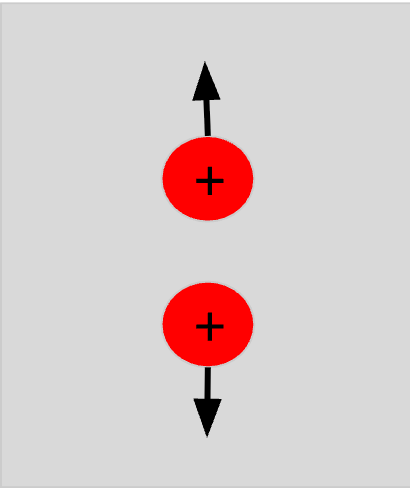

Experiments show that when two bodies interact, the force they exert on each other is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. This is referred to as Newton’s third law of motion.

One force is called action force and the other force is called reaction force. Together, they are referred to as an action-reaction pair since they always act together7.

, then the wall (B) exerts an equal and opposite force on the person (A) given by

, then the wall (B) exerts an equal and opposite force on the person (A) given by  .

.In equation form, this can be written as;

…..(26)

…..(26)

It is important to remember that the action and reaction force act on different bodies. For this reason, in a free body diagram8 of a certain body, you can never include both the action and reaction force because free body diagrams only include forces acting on the body, not the force that the body exerts on others. For example, in figure 13, the free body diagram for the wall (B) will look as follows:

), normal force (

), normal force ( ) and force that the person (A) exerts on it (

) and force that the person (A) exerts on it ( ). You would not include the force that the wall exerts on the person (

). You would not include the force that the wall exerts on the person ( ).

).Action and Reaction force doesn’t have to be a contact force. Long-range forces also exert equal and opposite force on each other in accordance with Newton’s third law of motion. When a ball is in free fall under the influence of gravity, it exerts an equal and opposite force on Earth. As a result, both ball and Earth accelerate towards each other! However, the mass of Earth is much larger than the ball and so it’s acceleration is almost negligible, but not zero!

Additional Topics (Young et al., 2016)

Friction Forces

Force of friction is a contact force. It has many day-to-day applications. Without the force of friction, it would be impossible to move forward while walking or use a parachute to safely land on Earth.

Kinetic and Static Friction

and a component parallel to the surface,

and a component parallel to the surface,  .

.Figure 16 shows a block resting on a surface and a force (push or pull) is applied to it. The surface exerts a contact force on the block which is composed of a perpendicular component called the normal force, ![]() and a parallel component called the friction force,

and a parallel component called the friction force, ![]() 9. Friction force is exerted in a direction such that it opposes any relative motion between the block and the surface.

9. Friction force is exerted in a direction such that it opposes any relative motion between the block and the surface.

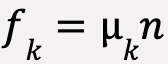

When a block slides down a surface, the kind of friction force that acts on it is called kinetic friction force,  . The word ‘kinetic’ refers to the fact that this kind of friction force acts when two objects (or surfaces) are moving relative to each other.

. The word ‘kinetic’ refers to the fact that this kind of friction force acts when two objects (or surfaces) are moving relative to each other.

Experiments have shown that;

…..(27)

…..(27)

Note: Equation 2710 is a scalar (not vector) relationship between magnitude of kinetic friction force, fk and magnitude of normal force, n because the two forces always act perpendicular to each other. ![]() is defined as the coefficient of kinetic friction and is unit-less. Smaller is the friction between the surfaces (slipperier is the surface), smaller is the value of

is defined as the coefficient of kinetic friction and is unit-less. Smaller is the friction between the surfaces (slipperier is the surface), smaller is the value of ![]() .

.

In the absence of relative motion between two bodies, such that a force applied to a block yields no motion, the friction force is exactly equal and opposite to the applied force and is referred to as static friction force, ![]() .

.

Experiments have shown that;

…..(28)

…..(28)

where (fs )max is the maximum static friction force and ![]() is the coefficient of static friction11. The value of static friction force can range between 0 and (fs )max which is given by

is the coefficient of static friction11. The value of static friction force can range between 0 and (fs )max which is given by  .

.

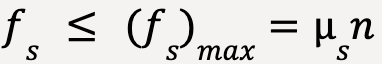

To understand (fs )max better, consider the following example;

Between time t = 0s and t = 1s, the block is sitting at rest on a surface with no external force, F applied to it. The only forces acting on it are in the y-direction, which include the block’s weight, w and normal force exerted by the surface, n. The two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction and thus  = 0. In this case, the external force,

= 0. In this case, the external force,

F = 0…..(29)

At time t = 1s, you start to apply force on the block and gradually increase it. However, for time t greater than 1s and less than 3s (1s < t < 3s), the block remains at rest. This is because the force of friction, fs is equal to the applied external force, F and fs is less than the maximum static friction force that can be attained in this case.

…..(30)

…..(30)

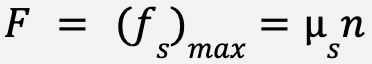

At t = 3s, the static force of friction, fs reaches a critical point where it becomes equal to (fs)max and the box is just about to begin sliding.

…..(31)

…..(31)

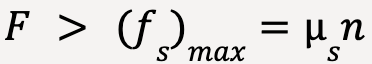

As soon as the applied force becomes greater than (fs)max, in this case for t > 3s, the block starts to slide (or breaks loose from the surface).

…..(32)

…..(32)

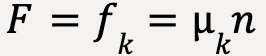

Beyond t = 3s, box is moving with a constant velocity along the surface (given that the applied force is equal to the force of friction at all times). At this point, the only force of friction acting on it is the kinetic force of friction12.

…..(33)

…..(33)

Note: as shown in the graph in figure 17, kinetic force of friction is generally less than the maximum static force of friction (or the coefficient of kinetic friction is generally less than the coefficient of static friction). This is why it is generally harder to get the block moving but once it begins to move, it is easier to pull or push it with constant velocity13. For example, for steel on steel, ![]() = 0.74 whereas

= 0.74 whereas ![]() = 0.57.

= 0.57.

Rolling Friction

It is usually easy to roll a tire down a surface instead of sliding it. This is where rolling friction comes into play.

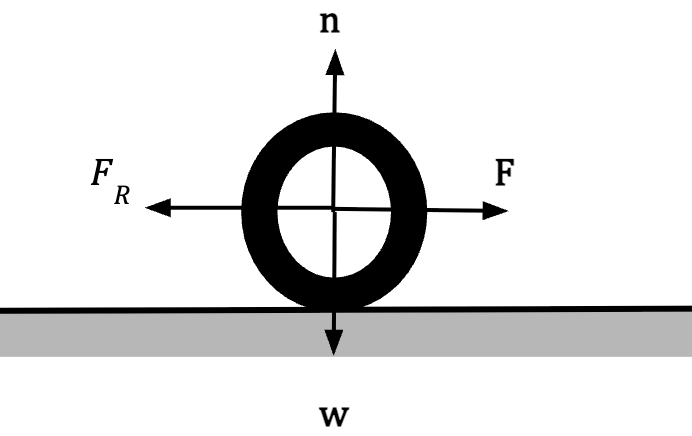

Let’s say you are rolling a tire down the sidewalk by applying a force F such that the tire is moving with constant speed. Note: F is applied horizontally and the object must be moving on a flat surface.

For tire to move at a constant speed;

=0…..(34)

=0…..(34)

F = FR…..(35)

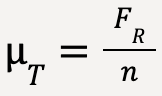

FR is called the rolling resistance force which is exerted by the surface on the tire to oppose it’s motion. Then the coefficient of rolling friction or  (referred to as tractive resistance by engineers) is equal to;

(referred to as tractive resistance by engineers) is equal to;

…..(36)

…..(36)

where n is the normal force exerted by the surface and is equal to the tire’s weight14.

For example, for steel wheels on steel rails,  is between 0.002 and 0.003.

is between 0.002 and 0.003.

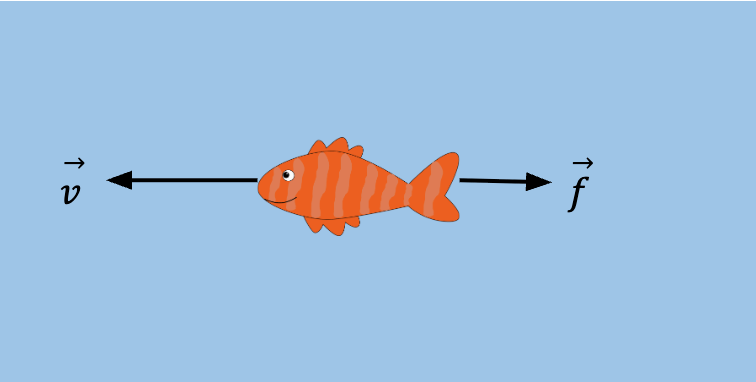

Fluid Resistance and Terminal Speed

Fluid resistance is defined as the force that a fluid (gas or liquid) exerts on a body as it moves through it. For instance, for a fish swimming in the ocean, fish exerts a force on the water by displacing it and in accordance with Newton’s third law, the water exerts a force on the fish that opposes it’s motion.

acts in a direction opposite to the direction of motion.

acts in a direction opposite to the direction of motion.The magnitude of fluid resistance depends on the speed of the moving body. It usually increases as the speed of the body increases. Additionally, it always acts in a direction that opposes the relative motion of the body with respect to the fluid.

For small objects (e.g. dust particle in air etc.) moving at low speeds, fluid resistance, f is given by;

f = kv…..(37)

where k is a proportionality constant and it depends on the body’s size and shape, as well as the properties of the fluid. It has units of N•s/m.

For larger objects (e.g. airplane etc.) moving with high speeds through air, fluid resistance, f (or air drag or simply drag) is given by;

f = Dv2…..(38)

where D is a constant that depends on the body’s size and shape, as well as the density of air. It has units of N•s2/m2.

Since fluid resistance varies with speed of the object, net force acting on a body falling in a fluid is not constant and so isn’t the acceleration. This means that constant acceleration equations are not valid in this case.

Consider a dust particle falling in the air, in which case, fluid resistance (or air resistance), f will equal kv.

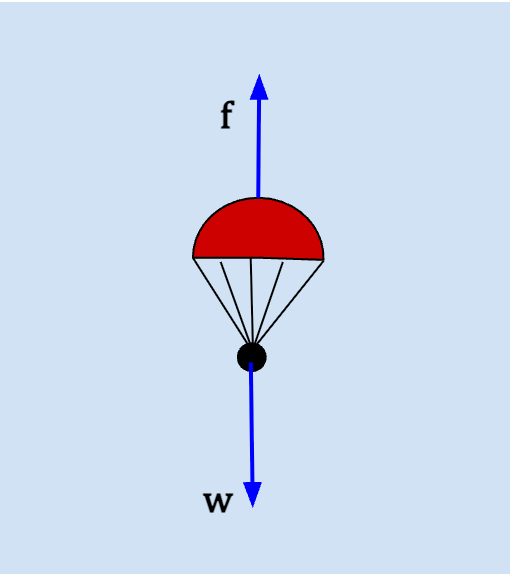

Figure 20: Free body diagram of a dust particle falling in the air.

Using Newton’s Second law along the y-direction (with downward direction taken as positive);

…..(39)

…..(39)

w – f = may…..(40)

mg – kvy = may…..(41)

The initial velocity of the dust particle is zero (vy = 0), which means that, initially, air resistance is zero and ay = g.

As the particle starts falling under the force of gravity, it’s speed increases and so does the air resistance which is directly proportional to the particle’s speed. At a certain time, the air resistance becomes equal to the particle’s weight and it’s acceleration becomes zero. Beyond this point there is no further increase in particle’s speed and it falls with constant velocity.

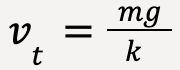

This final constant speed is referred to as the terminal speed of the particle.

When acceleration becomes zero, equation 41 becomes;

mg – kvy = 0…..(42)

kvy = mg…..(43)

…..(44)

…..(44)

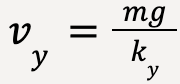

In general terms, for small objects travelling at low speeds, the terminal speed is given as;

…..(45)

…..(45)

If air resistance is negligible, dust particle will fall with constant acceleration, ay = g and we can use constant acceleration equations.

Let’s compare the equations and graphs of when there is air resistance and for when air resistance is negligible.

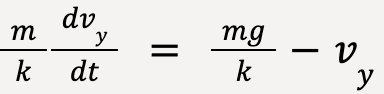

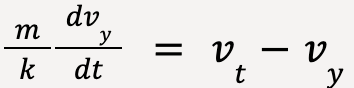

When air resistance is present, consider equation (41) and write ay = dvy/dt;

…..(46)

…..(46)

Dividing both sides by k;

…..(47)

…..(47)

From equation (45), vt = mg/k;

…..(48)

…..(48)

Rearranging terms;

…..(49)

…..(49)

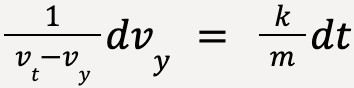

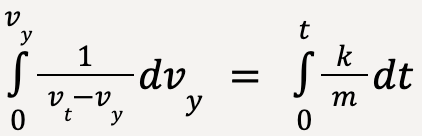

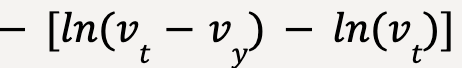

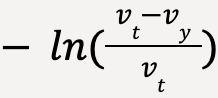

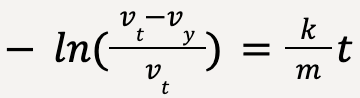

Integrating both sides;

…..(48)

…..(48)

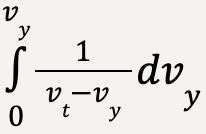

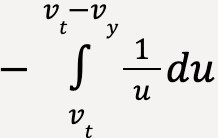

Solving the integral on the left hand side using substitution method (expand to see)

Let vt – vy = u and differentiating both sides; -dvy = du. Furthermore, to calculate limits in terms of u, when vy = 0; u = vt and when vy = vy; u = vt – vy.

…..(49)

…..(49)

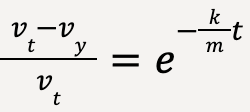

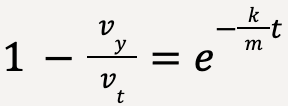

Moving the negative sign and taking exponent of both sides;

…..(50)

…..(50)

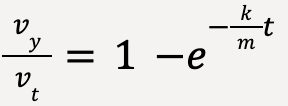

…..(51)

…..(51)

…..(52)

…..(52)

…..(53)

…..(53)

Note: that since e∞=0, vy will equal vt only when t approaches infinity and the dust particle will not be able to fall with terminal speed in reasonable amount of time.

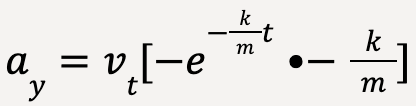

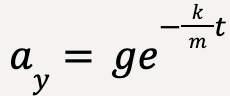

To find an expression for acceleration, ay, let’s take derivative of equation (53) with respect to dt;

…..(54)

…..(54)

…..(55)

…..(55)

…..(56)

…..(56)

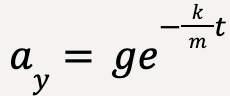

Substituting the value of vt from equation (45);

…..(57)

…..(57)

Again, when t goes to infinity, ay becomes constant and is equal to zero.

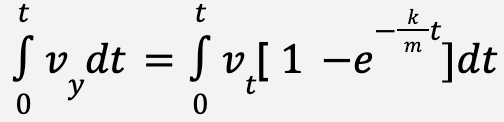

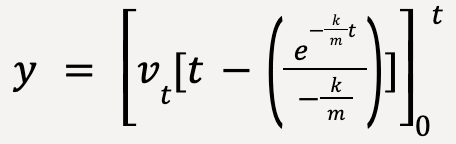

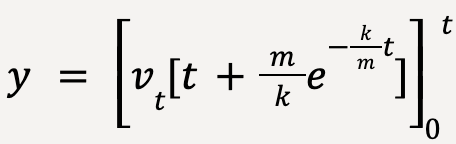

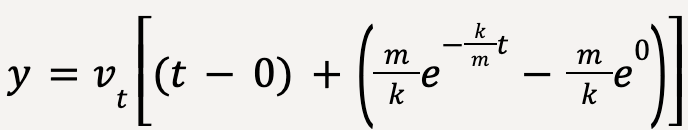

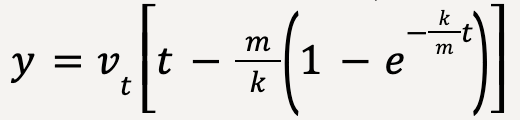

To find an expression for position, y, let’s take an integral of equation (53);

Multiply both sides by dt and integrate;

…..(58)

…..(58)

…..(59)

…..(59)

…..(60)

…..(60)

…..(61)

…..(61)

…..(62)

…..(62)

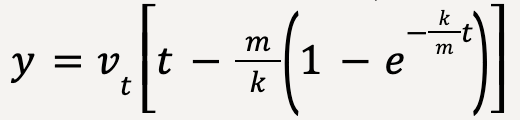

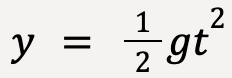

Comparing equations of motion for the two cases (given that at t=0, vy=0 and y=0):

| No Air Resistance | With Air Resistance | |

| Position |  |  |

| Velocity | vy = ayt |  |

| Acceleration | ay = g |  |

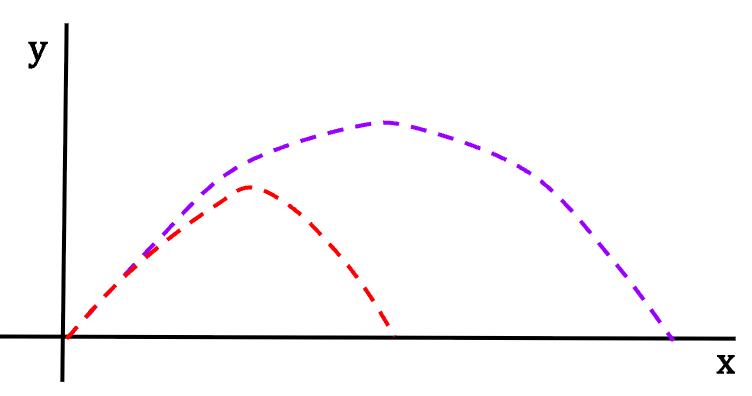

Let’s use these equations to plot graphs for position, velocity and acceleration.

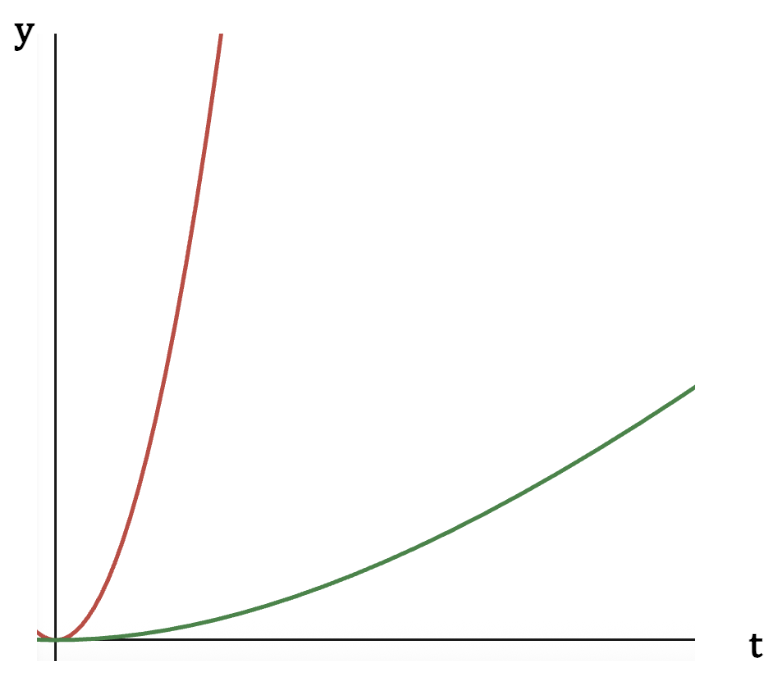

Graph of position vs. time

As discussed earlier, red curve for motion with no air resistance (means constant acceleration) resembles half a parabola. As expected, when air resistance is present, particle moves much slowly and therefore, compared to the red curve, it’s position varies at a slower pace with time.

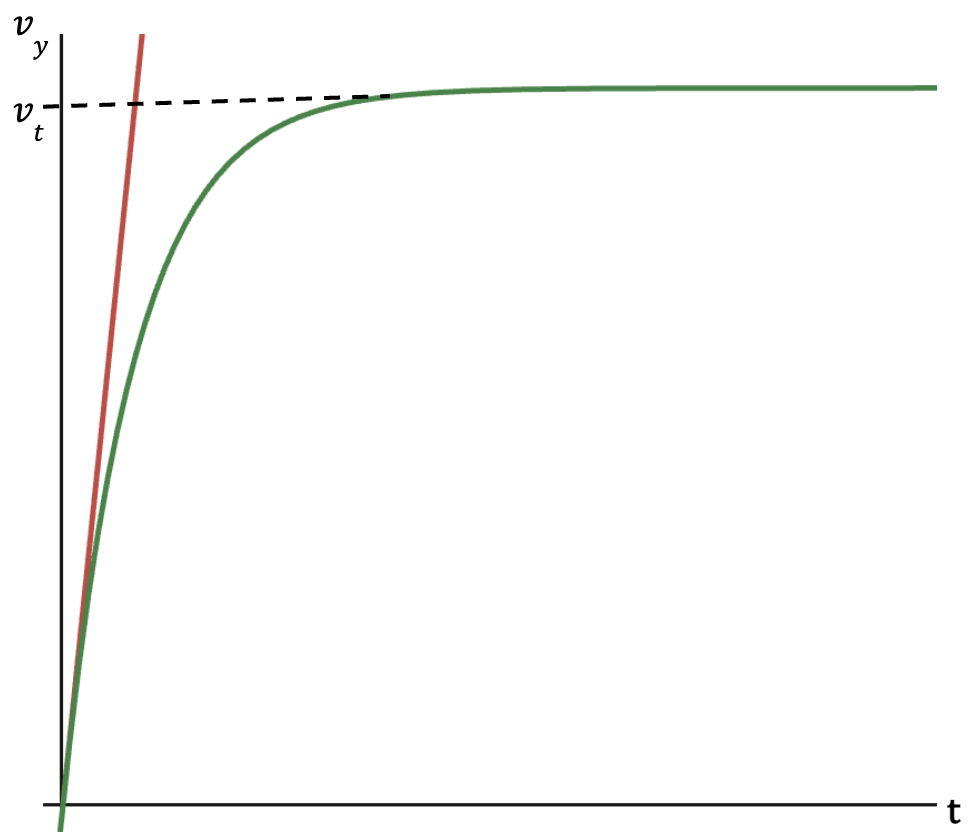

Graph of velocity vs. time

As discussed earlier, for constant acceleration with no air resistance, the velocity function is a straight line as is the case for the red curve and it continues to increase with time. However, when air resistance is present, the velocity function of the particle asymptotes yielding a final value (upper limit) given by the terminal velocity at which point particle’s acceleration becomes zero.

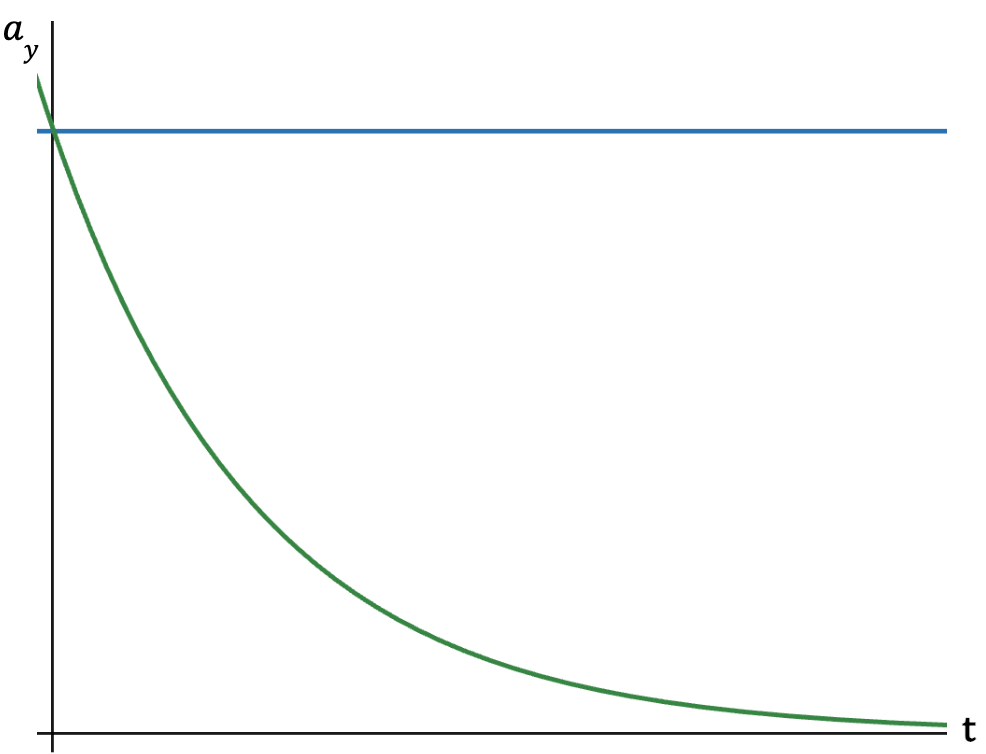

Graph of acceleration vs. time

For constant acceleration with no air resistance, the blue curve is a straight line. However, when air resistance is present, the acceleration exponentially drops because the opposing force is velocity dependent (f = kv). Ultimately it goes to zero and the particle at this point reaches terminal velocity.

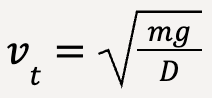

Similarly, for large objects falling at high speeds through air (f = Dv2), we can derive the formula for terminal speed using Newton’s second law of motion.

Consider a parachute carrying a load falling through the air.

Initially, the downward weight of the parachute is larger than the upward drag exerted by the air (w > f) and the parachute is accelerating downwards.

At a certain time during it’s decent, the weight of the parachute becomes equal to the air drag and it’s acceleration goes to zero;

…..(63)

…..(63)

w – f = 0…..(64)

mg = Dvt2…..(65)

Terminal speed for objects falling with high speed is then given as;

…..(66)

…..(66)

This is why objects that are heavier, fall with higher terminal speed since vt is directly proportional to  . This formula also explains why a sheet of paper falls slowly when compared to a crumpled piece of paper. They both have the same mass but D is smaller for the crumpled piece of paper and hence vt will be larger (vt is inversely proportional to

. This formula also explains why a sheet of paper falls slowly when compared to a crumpled piece of paper. They both have the same mass but D is smaller for the crumpled piece of paper and hence vt will be larger (vt is inversely proportional to  ).

).

The trajectory of an idealized projectile discussed earlier is unrealistic. Due to air drag, an actual projectile will travel much less distance in both x- and y- direction. Additionally, the path covered by a projectile under the influence of air drag will not be parabolic.

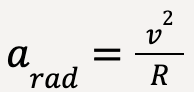

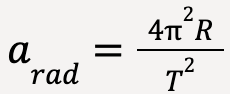

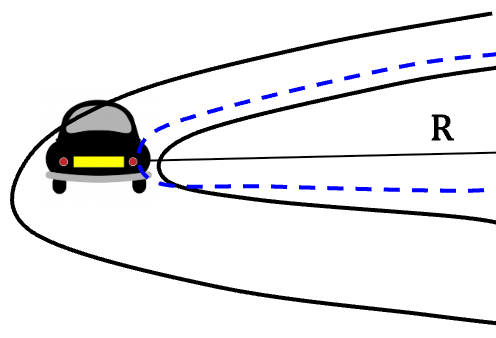

Dynamics of Circular Motion

As discussed earlier, the radial or centripetal acceleration for a body moving in a circle with constant speed is given by;

…..(67)

…..(67)

or

…..(68)

…..(68)

where v is the speed of the particle, R is the radius of the particle’s circular path and T is the period of motion.

For a particle of mass m, this force will equal;

…..(69)

…..(69)

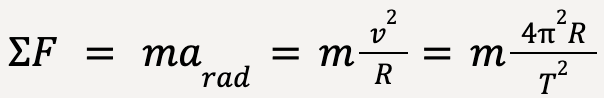

According to Newton’s second law, if the acceleration of a particle while moving in a circle is directed towards the centre of the circle, then there must be a net force acting in the same direction.

Note: Net force in the uniform circular motion can be made up of any number of forces as long as the resultant force directs towards the centre of the circle. Additionally, the object doesn’t have to complete a full circle for the force to act and equation (69) to hold.

In Figure (27), force given by equation (69) is acting as long as the particle is moving in a circular path which includes points t = t, 2t and 3t. However, as soon as the string breaks, this force ceases to exist and according to Newton’s first law, due to inertia the particle keeps going in a straight line at constant velocity in the absence of an external force15.

Banked Curves

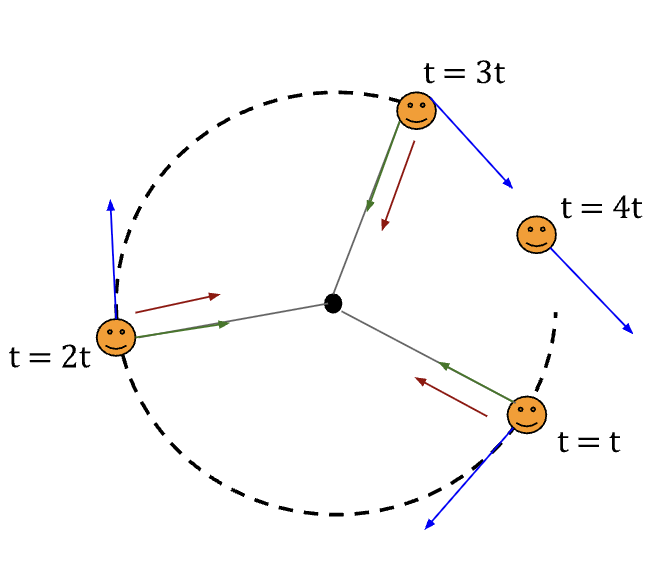

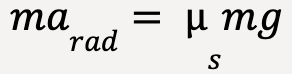

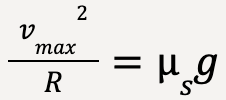

Consider a car of mass m travelling with velocity v on an unbanked flat curve with radius R.

For the car to keep turning with the road, a net force must act towards the centre of the circle. In absence of such a force, car will be pushed out of the curve, or more correctly, will keep going straight in accordance with Newton’s first law of motion.

Such a net force must then be provided by static force of friction because the car is neither sliding away from the centre nor towards the centre.

We can find the maximum velocity, vmax with which the car can round the curve in terms of coefficient of static friction, ![]() , acceleration due to gravity, g and radius of the circle R.

, acceleration due to gravity, g and radius of the circle R.

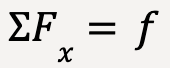

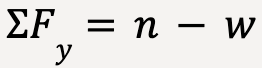

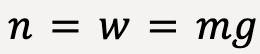

Applying Newton’s second law along x- and y-direction gives (taking positive x to be towards the right and positive y to be upwards) ;

…..(70)

…..(70)

…..(71)

…..(71)

…..(72)

…..(72)

![]() …..(73)

…..(73)

…..(74)

…..(74)

Note: To find vmax, we need to use the maximum value of static friction that the road can exert which is equal to  .

.

Substituting equation (74) in equation (71);

…..(75)

…..(75)

We know arad = v2/R;

…..(76)

…..(76)

…..(77)

…..(77)

Thus, the car can travel slower than this speed, but if it moves with a speed faster than vmax, it will skid.

However, if the road is icy and slippery with a very low coefficient of static friction, the inward net force will be negligible and car will not be able to round the curve.

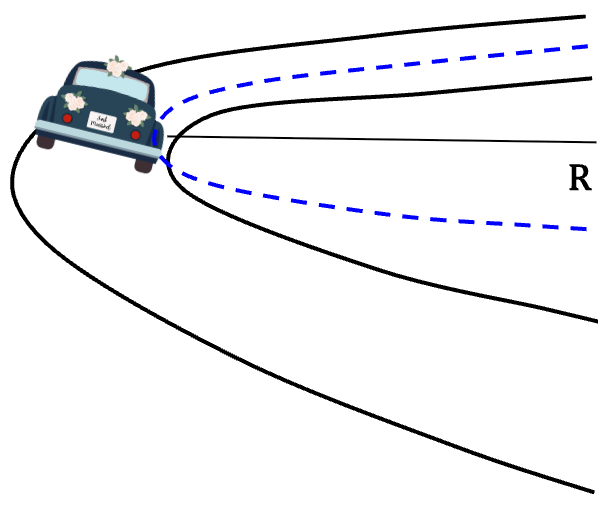

This is why engineers design banked curves so that cars don’t have to rely on friction to round a curve.

Since the curve is banked, a component of normal force acts towards the centre of the circle providing the required centripetal acceleration needed by the car to round the curve.

We can find a relationship between banked angle, ![]() and the car’s speed, v.

and the car’s speed, v.

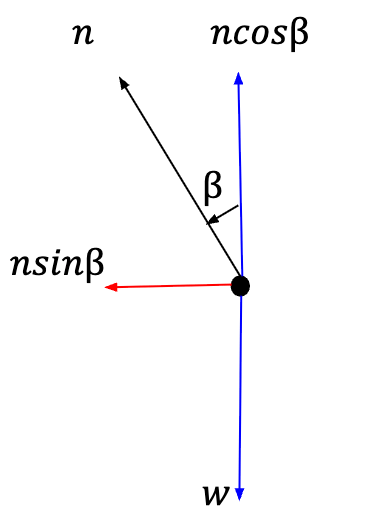

Applying Newton’s second law along the y-direction (taking positive y to be upwards);

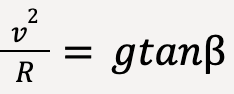

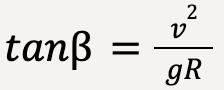

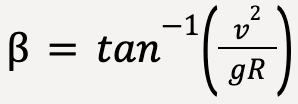

…..(78)

…..(78)

…..(79)

…..(79)

…..(80)

…..(80)

…..(81)

…..(81)

Applying Newton’s second law along the x-direction (taking positive x to be towards the right);

…..(82)

…..(82)

…..(83)

…..(83)

Substituting equation (81) into (83);

…..(84)

…..(84)

…..(85)

…..(85)

…..(86)

…..(86)

…..(87)

…..(87)

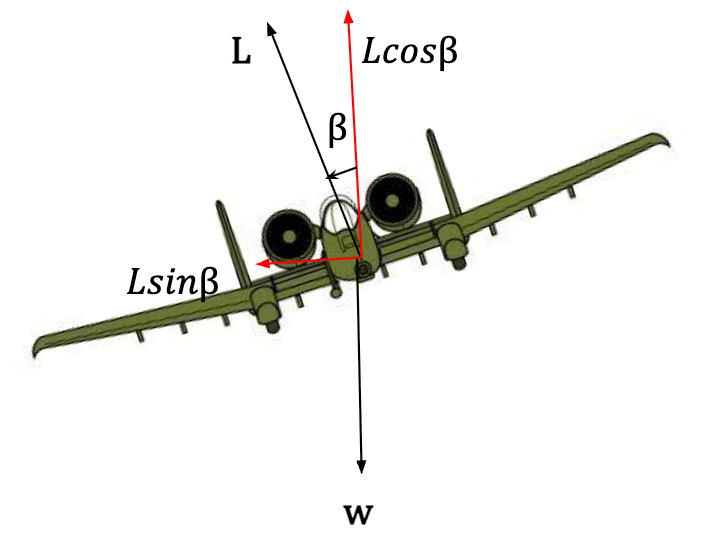

Flight of Airplanes

Airplanes use the same principle as banked curves on the road to make a turn. When a plane is flying straight at a constant speed, it’s weight is perfectly balanced by the upward force called lift16, ![]() . In order to make a turn, the pilot tilts the plane at an angle (say

. In order to make a turn, the pilot tilts the plane at an angle (say ![]() ) so that there is a horizontal component of Lift that provides the necessary centripetal acceleration.

) so that there is a horizontal component of Lift that provides the necessary centripetal acceleration.

Equation (87) applies to a plane making a turn. When making extremely tight turns at very high speeds, R is small and v is large. This means that in this case, ![]() becomes extremely large which corresponds to an angle,

becomes extremely large which corresponds to an angle, ![]() ~ 90°.

~ 90°.

As for the pilot in the plane,

Applying Newton’s second law along the y-direction;

…..(88)

…..(88)

…..(89)

…..(89)

…..(90)

…..(90)

…..(91)

…..(91)

The apparent weight of the pilot is given by equation (91). This is why when making sharp turns, ![]() becomes large and cos

becomes large and cos![]() becomes small. This leads to a very large n or apparent weight felt by the pilot which causes the pilot to lose consciousness!

becomes small. This leads to a very large n or apparent weight felt by the pilot which causes the pilot to lose consciousness!

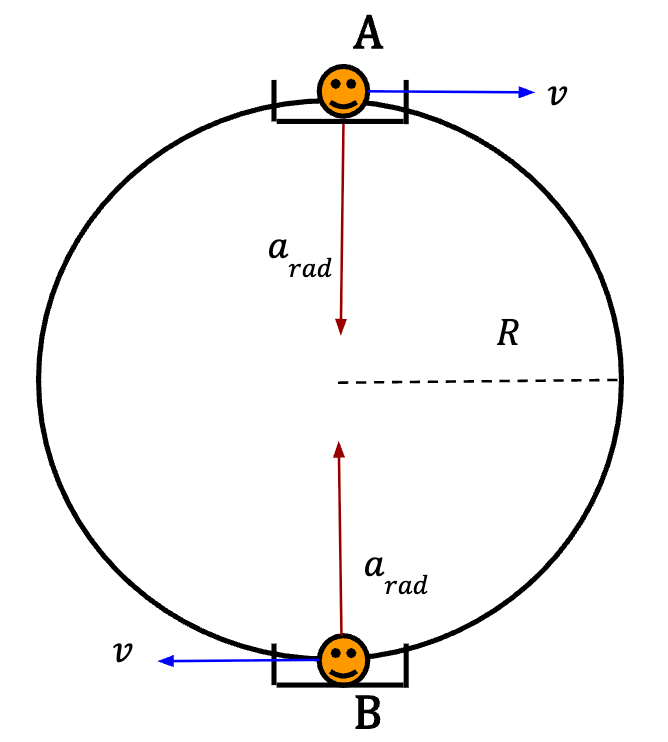

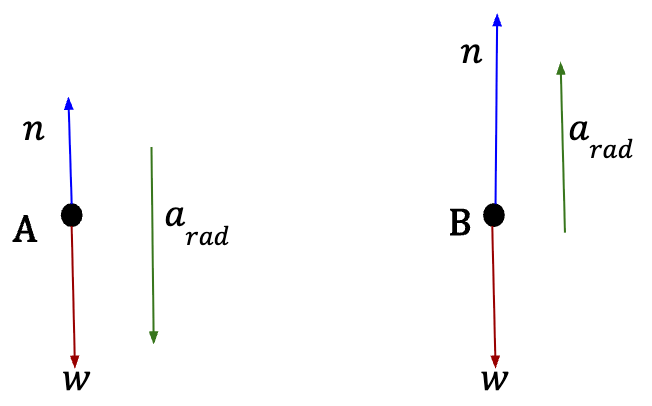

Motion in a Vertical Circle

The dynamics of motion in a vertical circle is the same as the principles defined for uniform circular motion in a horizontal plane but with one exception: the weight of the body needs to be treated with care.

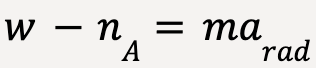

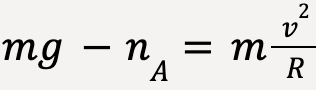

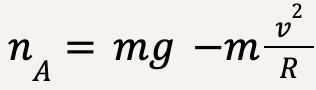

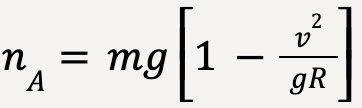

At point A (taking positive y-direction to be downwards);

…..(92)

…..(92)

…..(93)

…..(93)

…..(94)

…..(94)

…..(95)

…..(95)

…..(96)

…..(96)

At point B (taking positive y-direction to be upwards);

…..(97)

…..(97)

…..(98)

…..(98)

…..(99)

…..(99)

…..(100)

…..(100)

…..(101)

…..(101)

At point A, particle’s apparent weight is less than it’s true weight which equals mg. At point B, the particle’s apparent weight is more than it’s true weight.

Fundamental Forces of Nature

Four Classes:

- Gravitational Interactions

- Electromagnetic Interactions

- Strong Interaction

- Weak Interaction

Gravitational Interactions

Gravitational interaction arises from a body’s mass that exerts a pull on other objects in it’s surroundings. For instance, Sun’s gravitational force on Earth results in the periodic motion of Earth around the Sun.

Electromagnetic Interactions

Electromagnetic interactions involve electric and magnetic forces. Due to the presence of negative and positive electric charges, atoms exert electrical force on other atoms and molecules. Magnetic force arises from the motion of these electrical charges.

Note: At atomic scale, gravitational interaction is insignificant when compared to electrical interaction (gravitational interaction<<<<electrical interaction). On macro scale, electrical interaction is not important because positive and negative charges are usually present in equal numbers but gravitational interaction is significant.

Strong Interaction

Strong interaction acts within a very short range but is very powerful. It keeps a nucleus (neutrons + protons) together which would otherwise be pulled apart by positively charged protons repelling each other.

Weak Interaction

Like strong interaction, it acts within a very short range. Inside a radioactive nucleus, when a neutron converts to a proton, it emits an electron and an antineutrino. This conversion is referred to as beta decay. It’s called a weak interaction because the ejected particle antineutrino is nearly massless and does not interact with ordinary matter.

- Young, H.D. et al. (2016) Sears and Zemansky’s university physics: With modern physics. 14th edn. Boston: Pearson. ↩︎

- Newton’s second law can be applied to composite bodies to easily find the acceleration of the system by considering the two bodies as one, with mass m1 + m2. However, it is only applicable if the magnitude and direction of acceleration are same for the two bodies. Two bodies can not be treated as one composite body if let’s say they have the same magnitude of acceleration but it’s acting in different directions or vice versa. ↩︎

- This equation is only valid for bodies whose mass is not changing. For instance, this equation will not hold for an accelerating rocket ship which is expelling fuel. ↩︎

- Weight acts on a body at all times. A body that is not accelerating still has force of gravity acting on it, but this force is canceled by a force of equal magnitude acting in the opposite direction. For example, a block sitting on the floor has it’s downward weight supported by the upward normal force, leading to zero net force and thus, zero acceleration. ↩︎

- This is defined as the equivalence principle, backbone of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. ↩︎

- In reality, the value of g varies between 9.78 to 9.82 m/s2 because Earth is not a perfect sphere and the value of g is affected by Earth’s rotation and orbital motion around the sun. ↩︎

- Either of the two forces acting between the two bodies can be action or reaction force. The wording sometimes leads to a misconception that there is a cause-and-effect relationship, such that the action force must cause the reaction force, which is not true. ↩︎

- A free-body diagram as shown in figure 14 displays all the forces acting on a certain body, in this case, the wall. All these forces acting on the body make up

when using Newton’s first and second law of motion. Be mindful to not include forces that the body exerts on it’s surroundings. When using Newton’s third law, identify which of the two forces from the action-reaction pair acts on the body in question and disregard the other force. Remember that both action and reaction force can never be included in the same free-body diagram because they always act on different bodies. ↩︎

when using Newton’s first and second law of motion. Be mindful to not include forces that the body exerts on it’s surroundings. When using Newton’s third law, identify which of the two forces from the action-reaction pair acts on the body in question and disregard the other force. Remember that both action and reaction force can never be included in the same free-body diagram because they always act on different bodies. ↩︎ - Note: If the surface is frictionless, then it exerts only normal force on the block. ↩︎

- This equation is an approximate expression for the friction force acting between two surfaces moving relative to each other. It does not represent the complex relationship that exists between the molecules of two surfaces. In reality, friction occurs due to bonds that constantly form and break between the molecules at points that come in contact with each other. Larger is the number of bonds, greater is the kinetic force of friction. This is why sometimes very smooth surfaces can result in increased friction because it allows for more bonds to be formed between the molecules of the two surfaces. A layer of oil reduces friction because it prevents these bonds from forming by reducing contact between the molecules. ↩︎

- Note: Like force of kinetic friction, this relationship is scalar, meaning it is between the magnitude of force of static friction and magnitude of the normal force. ↩︎

- Between t = 3s and t = 4s, the saw-toothed shape for the kinetic force of friction reflects the complex relationship between the molecules of the block and the surface (as discussed earlier). However, it is safe to assume that kinetic force of friction is constant during this time because the box is moving with constant velocity. ↩︎

- Remember that the force of friction depends on the velocity of the moving body but this effect can usually be ignored for kinetic force of friction. ↩︎

- Equation 36 is a scalar relationship. ↩︎

- Avoid using the term centrifugal force to describe motion in a circle. This can lead to incorrect assumptions. For instance, when a car is taking a turn and you move to the outside of the car, it seems as though a force pushed you out. However, this is wrong. What happens is that when the car takes a turn, due to inertia, you keep going straight because there is no force acting on you and as a result you hit the outside of the car. ↩︎

- Lift is the upward force exerted on the wings of a plane by the air in reaction to force exerted by the wings on the air as it moves through it (Newton’s third law of motion). ↩︎